The Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque (Koski Mehmed-pašina džamija) is one of the three originally domed mosques in Mostar, Bosnia and Hercegovina. It stands not only as one of the city's most magnificent Ottoman mosques, but also as one of its most distinguished architectural landmarks. Alongside the Karađoz Beg Mosque and the Old Bridge, it ranks among the foremost symbols of Mostar's cultural pride and historical identity.

Yet this mosque is more than a structure, and more than a place of worship. It is an idea, a sanctuary, and a monument that embodies a calling, evokes memory, and reflects a civilizational predilection. Constructed in 1617-the seventh mosque in Mostar's recorded history-it was founded by Koski Mehmed Pasha, a native of the city and a man renowned for his generosity as a waqif (endower). His administrative career within the Ottoman devlet was reportedly distinguished, and upon retiring in 1606, he turned his attention to his beloved hometown.

It was during this final chapter of his life that he initiated the construction of his mosque complex, which included not only the mosque itself but also a khanqah-madrasah and an ablution fountain.

Elsewhere in Mostar, he built a caravanserai whose revenues were designated to sustain the fountain. It is as if the benefactor wished to spend his remaining years enriching the city's urban fabric and expanding its avenues for intellectual and spiritual fulfillment. As if it were a time for giving back.

Koski Mehmed Pasha passed away in 1611, before the completion of his endowment. The task was fulfilled by his brother, Mahmud. How Koski Mehmed Pasha spent his final days, where he died, and where he was laid to rest remains unknown. It is an enduring mystery, as if veiled by the silence of the very sanctuary he envisioned.

This foundational emphasis shaped not only the structural logic but also the symbolic grammar of the edifice. He further notes that the massive masonry units, quarried from nearby terrain, must have been transported to the construction site by an immense force, underscoring the monumental will that animated the project.

Evliya Celebi described the mosque as being in excellent condition, sheathed in blue lead, and resembling a royal sanctuary. It ranks second only to the Karađoz Beg Mosque - unsurprisingly so, as it closely emulates its architectural predecessor, almost to the letter. In its foundational footprint, the mosque measures 12.80 meters in length and 12.70 meters in width, just 20 and 30 centimeters shorter, respectively, than the dimensions of the Karađoz Beg Mosque. This yields a total area of 162.56 square meters, making it just 6.44 square meters smaller than its architectural model, the Karađoz Beg Mosque.

Given that the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque is, in many respects, a near replica of the Karađoz Beg Mosque, only its distinct structural and functional features will be highlighted in the discussion that follows.

This departure from the decorative style of the Karađoz Beg Mosque appears intentional, asserting through the most visually prominent external element that while the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque emulates its predecessor in many respects, it nonetheless preserves and confidently expresses its own architectural and artistic identity. It is not a mere imitation, but a stylistic supplement; it is an enrichment and diversification of the shared tradition. Seventy-eight stone steps spiral upward within the minaret, culminating at the balcony, while its hollow shaft maintains a diameter of 1.30 meters.

Not only this minaret, but the minaret typology at large, is to be understood as a refined vertical conduit and an axis of ascent, orientation, and elevated perspective. It invites the human spirit to rise, to ascend through spiritual flights towards higher vantage points from which to observe, appreciate, and discern with greater clarity. In this sense, minarets beckon people to cultivate broader and more diverse perspectives for their lives, refusing to be confined-let alone enslaved-by the fleeting moment or the material plane. Life, accordingly, is to be lived with vertical awareness, not horizontal entrapment.

The ultimate truth cannot be unearthed from the soil of empirical inadequacy or the intellect of fallible man. It descends from above, from the Creator. And given that mosques serve as the paramount and most receptive collective repositories of that truth-akin to the heart at the personal level-their minarets symbolize extended hands, spiritual eagerness, and even sacred curiosity. Such is a posture both willing and ready to receive the descending truth.

The underlying message is metaphysical: that higher standards and unifying principles bind and harmonize the world around us. These principles are not perceptible through the eyes or any material faculty. One must rise and awaken the sixth sense-the soul-to be admitted into this elevated realm.

Indeed, there exists a metaphysical harmony that governs its earthly counterparts, without which the latter would remain no more than appearances that are soulless, hollow, and aimless. Mere looks and outward manifestations may deceive, constrained as they are by the limitations of human perception and judgment. To truly grasp and appreciate the unfolding of existence, one requires an extended hand from "above", a transcendent aid that awakens the soul and illumines the path beyond the veil of the visible.

Curiously, the ablaq technique is not employed elsewhere in the mosque, in particular not in the arches supporting the small domes of the external portico, nor in those beneath the central dome. The portico's arches are left unadorned, exposing their raw masonry-a condition that may not have always prevailed.

Meanwhile, the redecorated arches inside the mosque have been embellished with continuously unfolding bands of alternating colors and patterns, likely intended to echo the ethos of ablaq. Historically, the technique may have originated with the Ayyubids in the Middle East, was perfected by the Mamluks, and ultimately diversified and internationalized by the Ottomans. The Gazi Husrev Beg Mosque in Sarajevo stands as a prominent example of ablaq taking root in Bosnia.

At the core of this tympanum lies an exquisite calligraphic inscription rendered in a form that evokes the visual grammar of a tughra, which is the stylized monogram or imperial seal of an Ottoman sovereign, traditionally symbolizing authority and legitimacy. Yet, in this instance, the inscription is not a royal emblem but a Qur'anic excerpt shaped in the likeness of a tughra: "While he was standing in prayer in the chamber (al-mihrab)" (Alu ʿImran 39). While the use of calligraphy that mimics the tughra is common in Ottoman decorative arts, its placement above the minbar's door-featuring a verse that references the mihrab, albeit not as a niche but as a chamber dedicated to worship-is somewhat unexpected. It introduces a subtle thematic dissonance, as decorative convention typically aligns Qur'anic inscriptions with the spatial and functional identity of the architectural element they adorn.

A compelling counterpoint is found in the tympanum above the mihrab itself, which-though structurally similar to that of the minbar, but smaller in scale-exhibits a more coherent integration of form, function, and script. Piercing the qiblah wall and serving as its defining element, the mihrab's tympanum features a meticulously executed calligraphic inscription that is part of a Qur'anic verse: "So turn your face towards al-Masjid al-Haram" (al-Baqarah 144). In this case, the thematic and spatial resonance is precise: the inscription reinforces the directional and devotional function of the mihrab, achieving a unity of structure, symbolism, and script that the minbar's tympanum, despite its aesthetic refinement, to some extent lacks.

What captivates the eye is that twenty of these windows-excluding only the two lowest on each wall-are arched stained-glass compositions adorned with geometric latticework. These windows function as both luminous instruments and ornamental expressions. Their design comprises hexagonal cells bordered by small triangular motifs, collectively forming repeated hexagram or six-pointed star patterns. Rendered in vibrant hues of red, blue, yellow, and green, they diffuse and tint the incoming light, producing a mesmerizing interplay of color and shadow. As sunlight shifts in intensity and angle, the patterns cast upon the walls and floor evolve in rhythm, animating the interior with a dynamic choreography of light.

This visual phenomenon transcends sheer aesthetics. It evokes emotional elevation and spiritual awakening, drawing the worshipper into a contemplative state attuned to the beauty of creation. In such moments, one is primed to acknowledge and appreciate the Creator, for a sincere recognition of creation's beauty inevitably leads to the recognition of the divine beauty that underlies it. The words of the Qur'an "Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth" (al-Nur 35) become not just a metaphysical truth but an experiential reality.

Indeed, the Prophet, Islam, and the Qur'an are described as lights, that is to say, the sources of guidance, spiritual sustenance, and existential clarity. Without light, neither physical nor spiritual existence is conceivable. The mission of Islam and its final Messenger is to lead humanity from the abyss of darkness into the radiance of divine light. Thus, entering a mosque is not simply a physical act but a symbolic passage: the worshipper, like the building itself, opens to the light, freely, vividly, and in abundance. The Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque stands as a luminous exemplar of this principle. It embodies the Islamic conception of enlightenment, not purely as a philosophical abstraction, but as a lived reality that permeates every facet of life, including the realms of art and architecture.

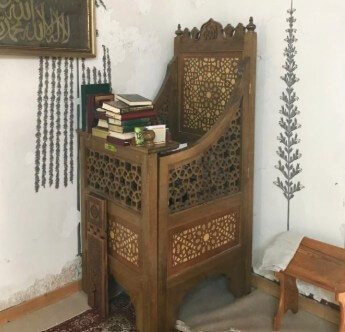

The presence of the kursi evokes the centrality of ʿilm-knowledge-in Islam, which is never to be confined to formal rituals or institutional settings. Knowledge is the soul of existence, the threshold of truth, and the beacon of civilizational progress. Despite its modest dimensions, the kursi is often enveloped in elaborate floral and geometric arabesque motifs. Observers may find themselves absorbed in its decorative richness, so much so that the material substrate and functional intent momentarily recede from view. The kursi appears almost wrapped in a visual tapestry, inviting the Muslim aesthetic impulse to manifest at its fullest. This predisposition has historically stirred and sustained the artistic creativity of Muslim artisans, who saw in the kursi not merely a utilitarian object but a canvas for spiritual and cultural expression. It is an opportunity that tradition never failed to seize.

Yet, in contemporary mosques, the kursi is increasingly relegated to a symbolic role. With the advent of advanced audio-visual technologies and spatial reconfigurations, its functional necessity has diminished. Today, it stands more as an artifact than an active instrument, an object of historical, artistic, and cultural significance. The same appears to be true for the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque. This shift explains why many modern mosques no longer incorporate the kursi into their architectural programs.

The imagery may well draw inspiration from the Qur'anic metaphor of a good word likened to a good tree, "whose root is firmly fixed and whose branches reach to the sky" (Ibrahim 24). In this context, the depicted trees symbolize more than ornamental flora; they evoke the kalimah tayyibah-the good and pure word-manifested either in the surrounding calligraphic writings or in the mosque itself, which, through its conceptual and existential substratum, articulates that word across every layer of its structure and function.

The mosque's interior is further enriched by a profusion of calligraphic inscriptions adorning its walls. These include Qur'anic verses and prominent religious refrains, framed within circular medallions, oval-shaped wreaths, and rectangular ornamental panels with carved and pointed ends, each contributing to the layered visual and spiritual narrative of the space.

Architecturally, the circular dome rests upon a square prayer hall via pendentives, a transitional device that generates eight arched supports. This structural arrangement produces eight roughly triangular zones-spandrels-bounded by the curves of adjoining arches. These spandrels have been utilized as decorative fields for inscribing eight revered names: Allah, Muhammad, the four Rightly Guided Caliphs-Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali-and the Prophet's grandsons, Hasan and Husayn. Each name occupies a single spandrel, forming a symmetrical and ideologically charged ring of sanctified memory.

This practice of inscribing sacred names in the upper sections of mosques, particularly beneath domes, became a hallmark of Ottoman architectural decoration. Its origins can be traced to earlier dynasties: the Fatimids, who employed mosque ornamentation to promote Shi'i doctrines; the Ayyubids and Mamluks, who responded after the fall of the Shi'a Fatimids with a counter-narrative that emphasized Sunni orthodoxy; and finally the Ottomans, who perfected this visual theology as a means of legitimizing their caliphate and asserting their leadership of the Sunni Muslim world. The inclusion of these names in mosque decoration thus served not merely as pious embellishment but as a declarative summary of Sunni ideology and civilizational continuity.

This decorative strategy is also evident in the Karađoz Beg Mosque. In contrast, the Nesuh-aga Mosque no longer displays such inscriptions due to a recent shift towards extreme decorative minimalism. However, in view of the Ottoman architectural logic and artistic vocabulary, it is highly probable that such inscriptions were part of its original configuration.

In this way, the mosque and the bridge form a visual alignment that-one can scarcely argue otherwise-was intentional. The mosque was deliberately positioned to secure a striking view of the bridge and the river simultaneously, serving as a source of psychological and emotional solace for its users. At the same time, it remains visibly prominent from the bridge itself, inviting attention to its presence and to the values it embodies. This axial relationship with the city's most iconic landmark renders the mosque a symbol, signpost, beacon, and sanctuary of Islam par excellence. It is a spatial proclamation. Even if one wished to, one could neither miss nor ignore the mosque and the messages it radiates.

The mosque's intimate interaction with its surrounding geography is both mesmerizing and deeply meaningful, conveying truths that transcend the visible. As a source of spiritual and intellectual vitality-especially given the presence of a khanqah-madrasah situated before it, and its historical role as a communal nucleus-the mosque's placement beside the Neretva River, perched above its stony bank, reflects an ontological appropriateness of the highest order. Universally, rivers and their waters are regarded as sources of life, embodiments of existential vitality and exuberance. More specifically, the stony ravines of Neretva-representing the broader craggy landscape from which the mosque's building stone was sourced-serve as the material and symbolic origin of the mosque's form. As the epitome of Mostar's rocky terrain and stone-laden topography, the river's rugged bank, into which the mosque is embedded, evokes the very materials used in its construction, all locally sourced, all organically integrated.

The message conveyed is clear: the mosque constitutes a micro-ecosystem nestled within a broader macro-ecosystem, both in harmonious dialogue and locally sustainable. They give to and receive from one another. Their points of convergence-physical and metaphysical-far outnumber their points of divergence. And even where they diverge, they do not exist in isolation or in realms governed by conflicting laws. Rather, they remain in indirect contact, perpetually gravitating towards one another as much materially as spiritually. In Islamic thought, the entire earth-and indeed the universe-is a mosque. The Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque is thus a segment of a vast, universal sanctuary, and its congregation merely a constituent part of a cosmic worshipping community that encompasses all creation. Spiritually speaking, the mosque, its terrain, and the river share a devotional wavelength and fulfill the same ontological purpose.

The people-users of the mosque-charged by their degrees of piety and intensities of virtue, can sense, consciously or otherwise, the otherworldly dynamics underpinning their mosque and its surroundings. This awareness fosters a profound sense of locational affinity: the mosque belongs to them, and they to it. All are home-grown, striving together towards greater heights of consequentiality and realization. Once inside, one should feel embraced by the mosque's native stone, timber, sand, clay, and water, and in turn, should embrace them. Through these elemental encounters, a sense of architectural and artistic home is cultivated. The worshipper belongs to the mosque and to the materials that constitute it, just as they, in their silent presence, belong to him.

To briefly illustrate the point: if a person is commanded to worship his Creator-Almighty Allah-constantly glorifying, praising, and prostrating to Him in reverent submission, the Qur'an simultaneously affirms that everything in the universe likewise worships, glorifies, praises, and prostrates before Him. According to the Islamic worldview, the life of creation in its totality is but a sweet and ceaseless hymn of deification, exaltation, and worship of the Creator. The only interruptions to this cosmic symphony are the brief, intermittent, and ultimately insignificant punctuations of disobedience by a segment of humankind and the jinn, exceptions that do not disturb in any way the overarching harmony of universal devotion.

For example, Allah says: "Do you not see that to Allah prostrates whoever is in the heavens and whoever is on the earth and the sun, the moon, the stars, the mountains, the trees, the moving creatures and many of the people? But upon many the punishment has been justified. And he whom Allah humiliates - for him there is no bestower of honor. Indeed, Allah does what He wills" (al-Hajj 18).

Also: "Whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth exalts and glorifies Allah, and He is the Exalted in Might, the Wise" (al-Hashr 1).

The mosque is bordered to the north by a market, flanked to the east and somewhat southeast by a line of shops, and edged to the west and the rest of the southeast by the winding course of the Neretva River. To shield the mosque from the market's bustle, a khanqah-madrasah was constructed, comprising nine equal-sized rooms that served as a hostel, and a significantly larger hall that initially hosted Sufi rituals and later accommodated study circles and public lectures.

These rooms are arranged parallel to the mosque, a layout intended both to define the northern boundary of the mosque ensemble and to preserve its inner devotional privacy and peace. The adjoining shops on the eastern and southeastern sides function similarly, as a protective shield, a spiritual bulwark. Though oriented towards worldly affairs, most of these shops belong(ed) to the mosque's waqf (endowment) and thus remain under its moral and administrative purview. Their presence forms a transitional buffer zone, mediating between the sanctified interior and the bustling urban exterior.

There is only one entrance into the mosque compound, discreetly positioned on the eastern side, piercing through the tightly knit alignment of shops. The entrance is by no means grand. Rather than ceremonially inviting one into sanctified space, it merely facilitates passage. Outwardly, it marks anything but a rite of passage, a deliberate understatement that reflects the mosque's original Sufi ethos.

In its initial phase, the mosque and its auxiliary structures embodied a distinct Sufi predilection anchored in a fusion of mystical devotion and mainstream Islamic rituals as well as practices. This hybrid model was common in Ottoman urban centers, where Sufism often functioned as the de facto expression of Islam. The presence of a substantial khanqah-madrasah fronting the mosque affirms this orientation. It was arguably the largest such establishment in Mostar, surpassing even the famed madrasah of the Karađoz Beg Mosque complex, which originally comprised five rooms and a lecture hall.

That was, indeed, Koski Mehmed Pasha's vision. His vakufnama (waqfiyya) reveals an explicit desire for his Sufi khanqah to be the unrivaled center of spiritual gravity in the region. Neither the modest maktabs nor the many madrasahs were conceived to match the architectural ambition and spiritual sobriety of this khanqah.

At first - as gauged from the above - the khanqah-madrasah served solely as a khanqah, which is a Sufi lodge and worship center, also called a tekke. How long it retained this function and when it transitioned into a madrasah remains uncertain. However, when Evliya Celebi visited Mostar in 1664, the building still functioned as a khanqah, as he does not list it among the city's madrasahs, though he does mention the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque as a prominent urban landmark. By 1796-and likely earlier-the khanqah had become a full-fledged madrasah, as evidenced by a grave within the mosque compound belonging to a person named Mulla Idris, son of Abdul Mumin Hodža. His tombstone inscription states that he died as a student of the (abutting) madrasah, confirming the building's educational role by that time.

Thus, sometime between 1664 and 1796, the Sufi khanqah underwent a full transformation into a mainstream public madrasah. With this shift, the entire mosque ensemble recalibrated, from a predominantly Sufi enclave into a conventional religious-civic institution oriented towards communal worship, education, and social development.

It is worth recalling that before the establishment of the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque complex with its Sufi leanings, the city of Blagaj located approximately thirteen kilometers southeast of Mostar had already earned a reputation as a Sufi center. Its famed tekke (khanqah), built by 1520 at the latest, stands beside the source of the Buna River near the city center. Tucked into a spectacular natural setting of rocky terrain, a breathtaking river spring, and a towering 200-meter karst cliff, the tekke exemplifies the Sufi ideal of spiritual retreat and natural synergy. Nestled at the foot of the cliff where the Buna emerges from a cave-one of Europe's largest and most powerful springs-the tekke's architectural and spiritual presence is dramatically magnified. The cliff forms its celestial backdrop; the river, its lateral element. It is a presence that eclipses the ordinary, a voice that outsoars the horizon.

Evliya Celebi, in his travelogue, praised the tekke's natural and spiritual marvels, affirming its age-old and historic reputation. It stands to reason that the original Sufi orientation of the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque complex-its location, its spatial grammar, and its relationship with nature-was inspired by the precedent of the Blagaj tekke complex. It may have been an attempt to replicate or extend Blagaj's spiritual sentiment into the urban fabric of Mostar, thereby further enriching and spiritualizing the fast-growing city.

Such was Blagaj's continuation - its co-existential, cooperative, and supportive "hand" extended towards Mostar. At any rate, it is a well-established historical fact that Blagaj's existence preceded that of Mostar, and that the latter emerged from the civilizational foundations laid by the former, in the sense that Mostar inherited Blagaj's regional significance, spiritual legacy, and socio-political continuity. This urban fraternity between two brother cities has long been constructive and affable. The Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque complex, though only a faint and evocative echo of Blagaj's tekke, stands as evidence of this spiritual kinship. So too does the fact that many waqifs (endowers) made charitable endowments in both cities, testifying to their shared spiritual economy and civilizational connection.

Yet, as Mostar's urban reality grew more layered and multifaceted, the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque complex gradually shifted from its Sufi inclination towards the standardized typology of civic mosque multiplexes, absorbing the rhythms and responsibilities of a burgeoning Ottoman city. Gradually, the mosque institution adopted a more pragmatic orientation, engaging with the everyday realities confronting people in their unvarnished form. It, however, would be far-fetched to claim that the mosque itself changed; rather, its horizons were broadened and its functions pragmatized, extending its reach without compromising the spiritual core.

No sooner had it become a full-fledged madrasah than the newly reconstituted institution emerged as a fertile source of knowledge and a generous conduit for scholars who would go on to illuminate not only Mostar but the wider region. It stood as a beacon of authentic human development and social advancement, recognized as essential prerequisites for any enduring civilizational achievement. Maintaining this function, it persisted in its service for three whole centuries, thereby preserving a tradition of scholarship, faith, and civic duty.

Unsurprisingly, the mosque-together with its fountain-was officially designated a protected cultural monument in 1950. Yet, precisely because it embodied architectural beauty, spiritual depth, and civilizational continuity, it also became "eye-catching" for all the wrong reasons to the adversaries of Mostar and of the religious and national identity of its Bosniak Muslim community. During the 1992-1995 Serbo-Croat aggression against the triad of Islam, Muslims, and Bosnia and Hercegovina, the visual symbols and the conceptual as well as physical embodiments of everything Bosniaks were, are, and aspire to be, were systematically targeted.

Mosques, as the most visible and vulnerable repositories of that identity, were intended to be eliminated or rendered dysfunctional, an undertaking in which, tragically and to a large extent, the enemies of Bosniaks, and indeed of humanity and civilization itself, were successful. Among the most prominent and thus most susceptible was the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque. Exactly because of its architectural distinction, spiritual symbolism, and memory-laden charisma, it became an "easy" target, suffering extensive damage. Its meticulous and complete restoration was finalized in 2001, when the mosque was ceremonially (re)opened. In 2004, the entire mosque ensemble was elevated to the status of a national monument, recognized for its architectural heritage merit and enduring historical value.

The spectacle is not only something to anticipate and bask in, but something to cherish long after. Depending on how one receives and manages the moment, the experience can be transformative, so much to see, contemplate, and absorb that one may lose the sense of groundedness, feeling suspended in air or, with a touch of imagination, as though one is flying. It is an unforgettable encounter that etches a wholly new visual and experiential version of Mostar into the visitor's memory, marked by awe, reflection, and a renewed sense of place.

However, the vogue is a two-edged sword. While the mosque today welcomes a steady stream of visitors-many of whom are non-Muslims-one must ask how effectively this rare, and for some perhaps once-in-a-lifetime, encounter with the House of Allah is being optimized to enlighten them about what Islam truly is, who Muslims truly are, and what mosques are meant to signify. More than architectural marvels, mosques are spiritual institutions anchored in revelation, community, and purpose. Their presence should awaken understanding, not merely admiration. Equally vital is the transmission of historical truth: the perennial Serbo-Croat intellectual, cultural, historical, and military aggressions against Bosnia and the Bosniaks, with the mosque serving as a symbolic and literal quintessence of that struggle, must be conveyed.

The fact that these visitors have come to the mosque-to the truth-rather than the truth being taken to them, is itself a remarkable achievement and a significant step in asserting and promoting historical and spiritual reality. Otherwise, the entire experience surrounding the mosque risks being diminished, downplayed, or even distorted. Given the linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity of the visitors-and the frequent presence of inadequately qualified guides-it is difficult to orally convey these layered messages. Yet much can be achieved through written materials: thoughtfully and comprehensively composed, translated into multiple languages, and distributed freely and casually. This is why it is said that tourism, for which much of the Muslim world is renowned, can be transformed into one of the most effective, friendly, and enlightening forms of da'wah-promoting the truth of Islam and the dignity of man and life, and offering people the opportunity to embrace and follow it.

What is unfolding today may be deemed moderately satisfactory - a step in the right direction, nevertheless far from the summit. As the adage goes, "the largest room in the world is the room for improvement." Complacency is a subtle adversary; to rest on one's laurels is to risk stagnation. While socio-cultural, economic, and touristic considerations are valid, they must never eclipse the mosque's ultimate religious-qua-civilizational role. That role must be elevated-placed on a pedestal and illumined in the public consciousness-for it is this essence that defines what mosques truly are and what should most deeply resonate with sincere visitors and honest seekers of both worldly and otherworldly truth. The mosque is not merely a structure of stone and ornament; it is a spiritual portal and a launchpad towards higher provinces of consequence, contentment, emotional fulfillment, and existential clarity. It is the locus where the transcendent dimensions of Islam-the only truth revealed to all prophets across the arc of human history-converge and come alive in the awakened heart, the enlightened mind, and the rightly calibrated trajectory of a believer's life.

To enter a mosque and engage in worship is to step into a microcosm of truth, life, providence, and destiny. It is to inhabit a trans-dimensional awareness that transcends the apparent constraints of time and space. In the mosque, the believer feels unshackled from the fetters of human smallness and terrestriality. He distinguishes that the spirit of truth, history, and the raison d'être of life itself has descended upon him, intersecting with his act of submission. He feels at home with his Creator, with His truth, and with his own eternal purpose. He is welcomed into a realm where he prepares his abode in the Hereafter. This spiritual trajectory echoes the supplication of Pharaoh's wife, who - confined to her terrestrial house, which functioned as her private sanctuary of worship in defiance of Pharaoh's tyranny - prayed: "My Lord, build for me near You a house in Paradise and save me from Pharaoh and his deeds and save me from the wrongdoing people" (al-Tahrim 11).

Thus, the Qur'an declares: "The mosques are for Allah, so do not invoke with Allah anyone" (al-Jinn 18). The Prophet affirmed: "Mosques are only for the remembrance of Allah, prayer, and the recitation of the Qur'an" (Sahih Muslim). He also said: "The most beloved places to Allah are the mosques," and "Whoever builds a mosque for Allah, Allah will build for him a house in Paradise" (Sahih al-Bukhari, Sahih Muslim). The Qur'an further proclaims: "The mosques of Allah are only to be maintained by those who believe in Allah and the Last Day and establish prayer and give zakah and fear none but Allah. It is they who are expected to be on true guidance" (al-Tawbah 18).

Non-Muslims, by virtue of their fitrah (primordial disposition), intellect, and intuition-gifts bestowed by Allah upon all humanity-may recognize that something extraordinary is unfolding within the mosque. They may conventionally describe this as peace, beauty, serenity, or harmony, which are terms that, under the ostensibly alluring but ultimately hollow mantle of postmodernism, risk becoming aestheticized clichés.

Nonetheless, such impressions merely graze the surface. A vast, unseen world of meaning and metaphysical wonder lies beyond the reach of the senses. It is our duty to guide non-Muslim visitors-gently, wisely, and truthfully-so they may do justice both to the mosque and to themselves. This task is not without its challenges, though. It runs counter to the materialist assumptions that undergird much of modern tourism and leisure culture. It demands intentionality, effort, and a principled commitment to truth.

Yet it remains a noble endeavor yielding profound and enduring rewards, both for the visitor and for the custodians of mosques.

Some scholars, concerned with the sanctity of the mosque, argue that non-Muslims should not be permitted to enter at all. But such a stance, while perhaps well-intentioned, neither aligns with the Prophetic example nor with the broader arc of Islamic history.

Non-Muslims should indeed be welcomed, but under conditions that uphold at once the ethics of conduct and the authenticity of the experience. For the mosque is not a museum, nor a monument to be admired from a distance. It is a living sanctuary, a house of divine presence, and a gateway to truth.