From mother to madrasa

I grew up reading the Qur'an on my mother's lap. It's usual, once Muslim children are about four or five, for their mothers to start reading the Qur'an and getting the child to repeat the words, again and again, till they become familiar and can be easily recited from memory.

Actually, I started a little late, when I was pushing six. In those days, we lived in a small town on the Pakistani side of the Punjab. After dinner every Thursday evening, my mother would shout: "Sipara time!" I would stop playing, run to her, jump on her lap, and put my left arm around her neck. She would open a slim, rather torn booklet, and start reading: Bismi llahi l-rahmainl-irahim. In the name of God, the beneficent, the merciful. I remember how she would pronounce each word distinctly.

A sipara contains a section of the Qur'an. The word "Qur'an" means reading; and the holy book is often described as "the noble reading". To make it easier to read, it is divided into 30 sections known in Arabic as juz-un. Sipara is the Urdu equivalent, sometimes shortened simply to para. Reading one para a day, you can complete the whole Qur'an in a month. This comes in handy during the fasting month of Ramadan when the whole Qur'an is read, one section on each of the 30 days, to vast gatherings at special evening prayer sessions. The emphasis on reading the Qur'an during Ramadan is because it was during this month that the first words of the Qur'an were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

Children begin their reading at the end of the book. So I started with the 30th sipara. It contains short chapters, or suras, some just a few verses long, all rather easy to commit to memory. When I had memorized most of the chapters in this sipara, and it was time to tackle the longer suras, my mother sent me to a madrasa in the local mosque. This is vaguely equivalent to Sunday school, but with rather more emphasis on the school, as the curriculum is set and the same everywhere: learning to read the Qur'an.

Most mosques have a madrasa, a religious school, attached to them. And I suppose my madrasa was like that in any mosque, anywhere in the world. It was a small, darkly lit room. Children would arrive at an appointed time, in my case after midday Friday prayers. On arriving we'd all perform the obligatory ritual of ablution. Then we'd take our places on small stools behind a long, narrow table. The imam sat on a chair in front of us, waving a long stick. We would be instructed to open our sipara on a specific page - and start reading aloud. If someone got the pronunciation wrong, or made some other mistake, down would come the stick. I don't remember anyone actually being hit; the punishment seemed to land on the table. But I do remember the rapid-fire swish and thwack frightened us all.

I wasn't enthusiastic about my madrasa lessons, which lasted about an hour. They lacked the loving touch of my mother. But I loved what happened afterwards. The classes were not graded: everyone from the locality came, all ages and stages mixed in the harmonics - to an untrained ear, cacophony - of reading aloud. So someone would always be about to reach the completion of the whole Qur'an. When they did, their family would celebrate with a generous distribution of sweetmeats. I would gorge myself and always got to take a plateful home.

A select number of students would manage to memorize the whole Qur'an. They would be honored with the title hafiz. And then their family's joy would know no bounds.

Of course, the classes I attended were for boys. But exactly the same classes were held for girls; how else would mothers be ready to teach their children? But, after the madrasa, the awful difference in attitudes to and provision of education for women in many Muslim countries never ceases to outrage me.

My lessons did not last long. When I was nine, my family moved to London, to Clapton Pond in Hackney. In the early 60s, there were few mosques in London. There was no chance of me going to a madrasa. So back I went to my mother - but her lap was now occupied by my younger sister. Besides, she expected me to read the Qur'an by myself. This wasn't really surprising, as I had reached the end of the 29th para. My mother was insistent that I start from the beginning again. But this time I had to read the words with meaning.

For Muslims, the Qur'an is the word of God. In fact, that's how we define a Muslim - someone who accepts the divine origins of the noble reading. To read the Qur'an is to see and hear the very words of God. When my mother was taking me through my first sipara, it was nothing like her reading me a bedtime story. When she taught me to read the Qur'an it was an act of worship and prayer. She was, in fact, teaching me how to pray.

Even before I started to read the Qur'an with meaning, I had developed emotional connections to the sacred book. I felt a deep love for the text; it grew just from the experience of learning. The glorious Qur'an, as far as my mother was concerned, was all about love. Love of God. Love of his words. It was a deep, all-pervasive, unconditional love - like that of a mother for her son.

I also felt reverence for the Qur'an. This came from watching how my mother approached it: with total respect and humility. And I felt fear. Somehow, reading the Qur'an always invoked the memory of the madrasa and the long bamboo stick. Swish! Later, I rationalized this fear as the apprehension of actually encountering the majesty of God.

In London, the ritual of reading the Qur'an changed. Both my parents worked from Monday to Friday. So Qur'an reading took place on Saturday mornings. (Sundays my mother devoted to a more profane ritual: she went, without fail, to the local fleapit to watch the latest offering from Bollywood.)

I would sit in front of my mother and read out some verses. She would explain their meaning in Urdu with the aid of a translation. I would then read out the English translation of the same verses. Then we would chat and disagree.

My first problem was with the Urdu translation. Urdu is an exquisite and poetic language. It is suffused with Arabic words. That's why those, like me, who read Urdu find it easy to read Arabic. But I found Urdu translations of the Qur'an to be rather strange. Worse: they were often at odds with English translations. Reading the Qur'an, I quickly realized, is one thing; understanding it is quite another.

Most of my life since adolescence has been a struggle with the meanings of the Qur'an. During my university years, when I was active in various student Islamic bodies, I joined a study group, an usra. We studied the Qur'an with the aid of a number of classical and contemporary commentaries, under the guidance of a well-known scholar. As my career developed, I attended innumerable conferences, visited many Muslim countries, and met many people who argued about the meanings of the sacred text. The more I learned about the Qur'an, and the more I engaged with it, the more intense my struggle became. The more I learnt of Muslims' intellectual history and thought about the differences and distinctions, as well as similarities, between classical and modern scholars, the more I had to struggle with what Muslims throughout their history have made of Islam.

Every Muslim will tell you the Qur'an is eternal. It is timeless, its words unchanged, it is ever present. The Qur'an addresses us directly, as it always has. But religious texts, by their very nature, are complex. And one of the most insistent commands in the Qur'an is: Think! Reflect! So the struggle to understand and interpret is our eternal challenge. There is no getting away from it.

The significance and meaning of the verses of the Qur'an have to be rediscovered by each generation. Contexts change, and old meanings, the customs born of old interpretations, can be suffocating. Or worse, they can be turned into means to oppress or oppose others.

These blogs will be a continuation of my struggle. I want to share what I understand and think of the Qur'an as a dynamic text, of whose relevance and implications for our time we have hardly scratched the surface. And, of course, that means reflecting on the thinking and ideas of other Muslims as well. I have no qualms in admitting I am not the most qualified person to talk about the Qur'an, let alone venture into the thorny territory of interpretation. I am not a hafiz (Quran reciter), or an imam( Islamic clergy), or an alim (a religious scholar) - though on certain bad days, I do imagine myself as a Muslim thinker of some repute. Worse: I don't even speak Arabic.

But the vast majority of Muslims are in exactly the same position as me. Indeed, of the 1.2 billion Muslims who populate the planet, only around 300 million are Arabic-speaking. In any case, modern Arabic comprises a great variety of dialects and is quite distinct from the Arabic of the Qur'an. Arabic speakers may have an advantage in pronouncing its words correctly, but they are in the same boat as everyone else when it comes to trying to discover the meaning and contemporary relevance of the Qur'an.

Before we get down to serious reading, I am going to devote the next two blogs to exploring the special nature of the Qur'an and discussing the basic rules for reading and interpreting the sacred text.

So, are you sitting comfortably?

Blogging the Qur'an

How should Islam's sacred book be read in the 21st century? How should non-Muslims interpret its message? In a year-long project, Ziauddin Sardar will read the Qur'an from beginning to end, discussing its verses, themes, language and meaning. Join in by emailing him at blogging.the.quran@guardian.co.uk. The blog will be launched on Monday on Comment is free

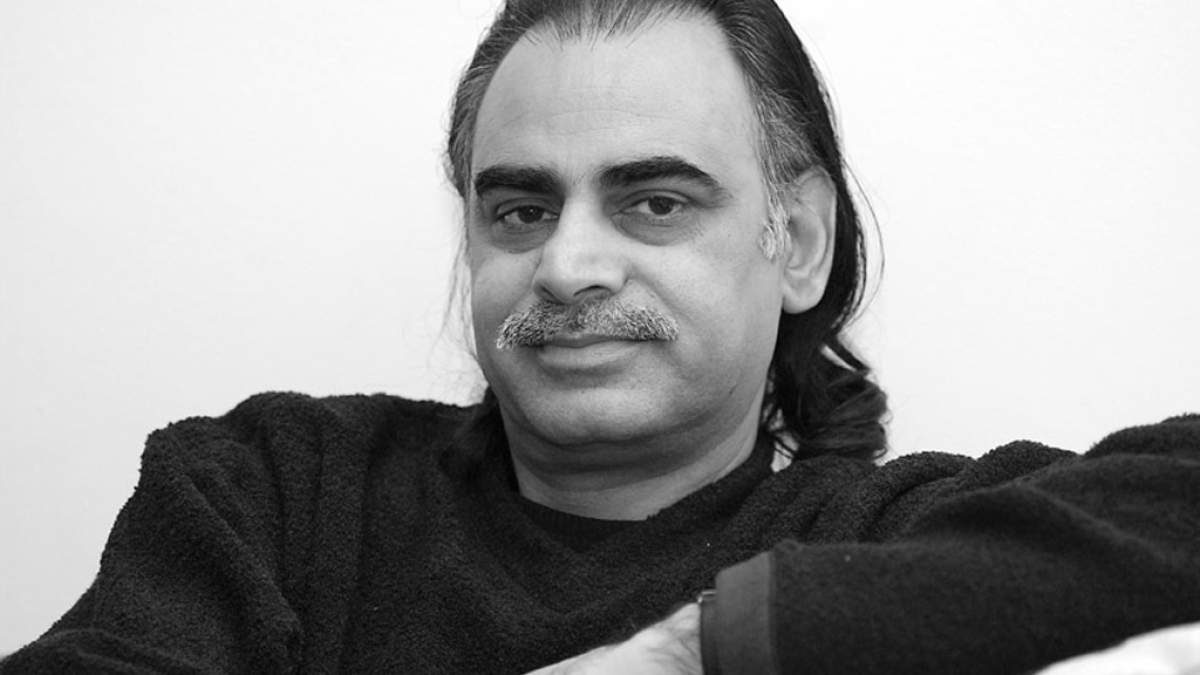

Ziauddin Sardar is a writer, broadcaster and cultural critic, and author of Desperately Seeking Paradise: Journeys of a Sceptical Muslim

Related Suggestions