The revolution will now be commercialized

In 1970, Gil Scott Heron, an African American poet and musician, wrote what has become possibly the definitive work on the spirit of revolution that swept the United States in the 1960s and early 1970s. Entitled "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised," these nine stanzas of poetry stand as a testament to all that revolution is and all that society has become. It is as true to today as it was in 1970.

But although the truth of the poem remains intact, the reality of society's approach to revolution has changed drastically. In fact, one might even argue that in the year 2000, the revolution will not only be televised, but it will be commercialized and merchandized as well.

This all hit me while browsing the shelves of a local book superstore. The fact that it was a superstore is important, because like any other superstore, it's focus is to provide large quantities of popular products, marketed to the lowest common denominator of societal interest. In no way can it be considered "niche" or "specialty."

What I found in the children's section of this store amazed me. Featured prominently at the beginning of one of the aisles, was an ad display for a children's picture book on the life of Malcolm X. The display stood not five feet from such children's book mainstays as Barney, Blue's Clues and the Teletubbies.

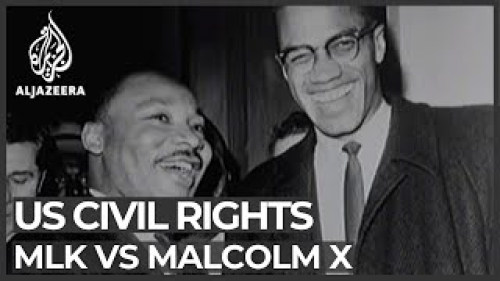

I had to blink and rub my eyes, because it was not long ago that Malcolm X took a distant back seat to Martin Luther King, Jr. in any discussion concerning the Black civil rights movement of the 1960s. I remember when Malcolm X was dismissed as a radical militant with dangerous political leanings. I remember when Malcolm X was the last figure one would expect to see in the children's literature section of a library, let alone on the shelves of a commercial bookseller.

Yet there before me stood Malcolm, the "American Muslim Martyr," illustrated and condensed for a child's level of comprehension.

I suppose I should think positively about the fact that mainstream America has chosen to embrace Malcolm X as an important figure in American history, even if only for the duration of Black History Month. Surely his acknowledgement can be seen as a step in the right direction with reference to the improvement of relations between the American establishment and the African American community. If Malcolm can be praised for the revolution in thought he inspired, then maybe justice and equality is indeed on the horizon.

But at another level I cannot help but feel that the popularization of Malcolm X and various movements of societal change has been a detriment to the realization of their goals.

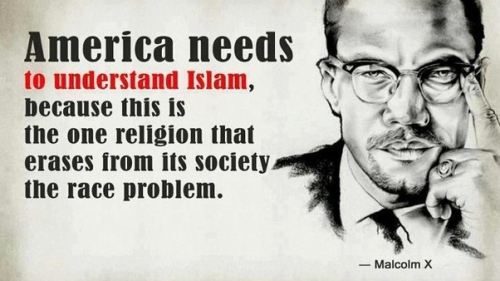

When Spike Lee made his movie on the life of Malcolm X, there seemed to be greater interest in movie merchandise than the message of true Islam Malcolm propagated in the last prolific year of his life. Figures like Jesse Jackson and John Lewis are now ensconced members of the political establishment. And artists like Public Enemy and Rage Against the Machine seem to speak to a middle class youth audience that is more interested in the image of revolution and change than the actual work it takes to improve the lot of the downtrodden and the oppressed.

For contemporary Muslims this popularization of thought on reform is problematic. In so many ways, Islam brings a revolution in thought that, at present, is being met with societal resistance. What happens if, in 15 years, America popularizes Islam to the point that certain Islamic truths and practices are recognized and popularized, but others fall to the wayside? What happens if Ramadhan is declared a national holiday, but the deeper messages of Islam are passed off as a revolutionary afterthought?

I wonder what Gil Scott Heron thinks of all this?

Ali Asadullah is the Editor of iviews.com

Related Suggestions

In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, and such (and all) material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.