Prayer is one of the five pillars of Islam. This article explains common features of Islamic prayer, such as the call to prayer, daily timings and the direction of prayer. It also explores the linguistic, geographic and sectarian diversity of prayer in Islam.

In Islam, prayer, supplication, purification and most ritual actions are considered acts of worship (ʽibadat). The most well-known, and an obligatory, act in Islam is the performance of the five daily prayers, which in Arabic is known as salah (often written salat). In the Qur'an, the Arabic word salah means to demonstrate servitude to God by means of certain actions. The same term is used in many languages throughout contemporary Muslim-majority countries, such as in Malay and Swahili. In other languages, such as Persian, Urdu and Turkish, the term that is commonly used for the ritual prayer is namaz. However, regardless of the term used, the ritual prayer and most other worship is always performed in Arabic throughout the Muslim world and is nearly identical with only slight variations. Different terms reflect the geographical and linguistic diversity of the Muslim world, but the Arabic language unifies them.

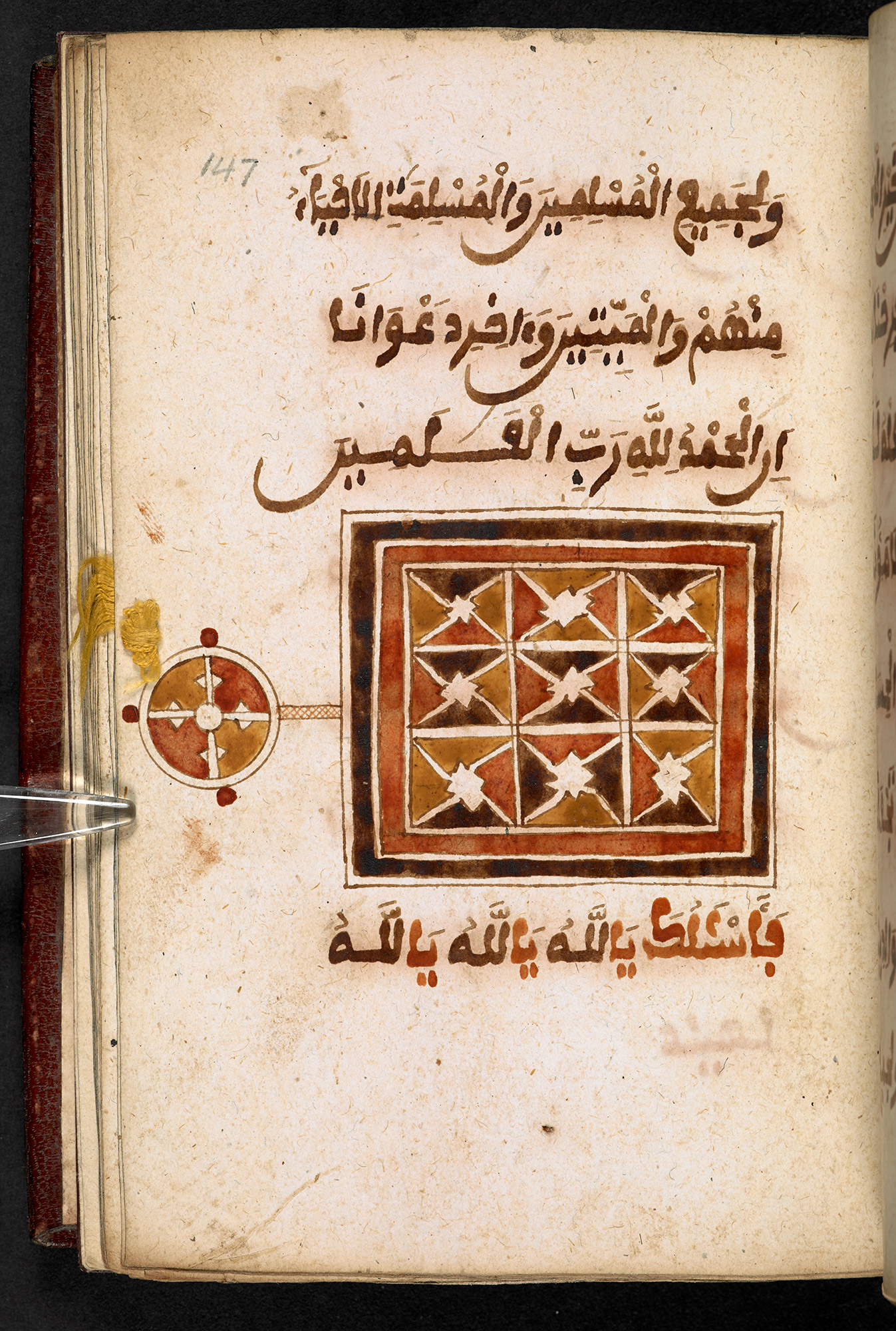

This is a finely scribed and illuminated West African copy of the Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt, a popular prayer book by the Moroccan author Muḥammad Ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī (photo: British Library).

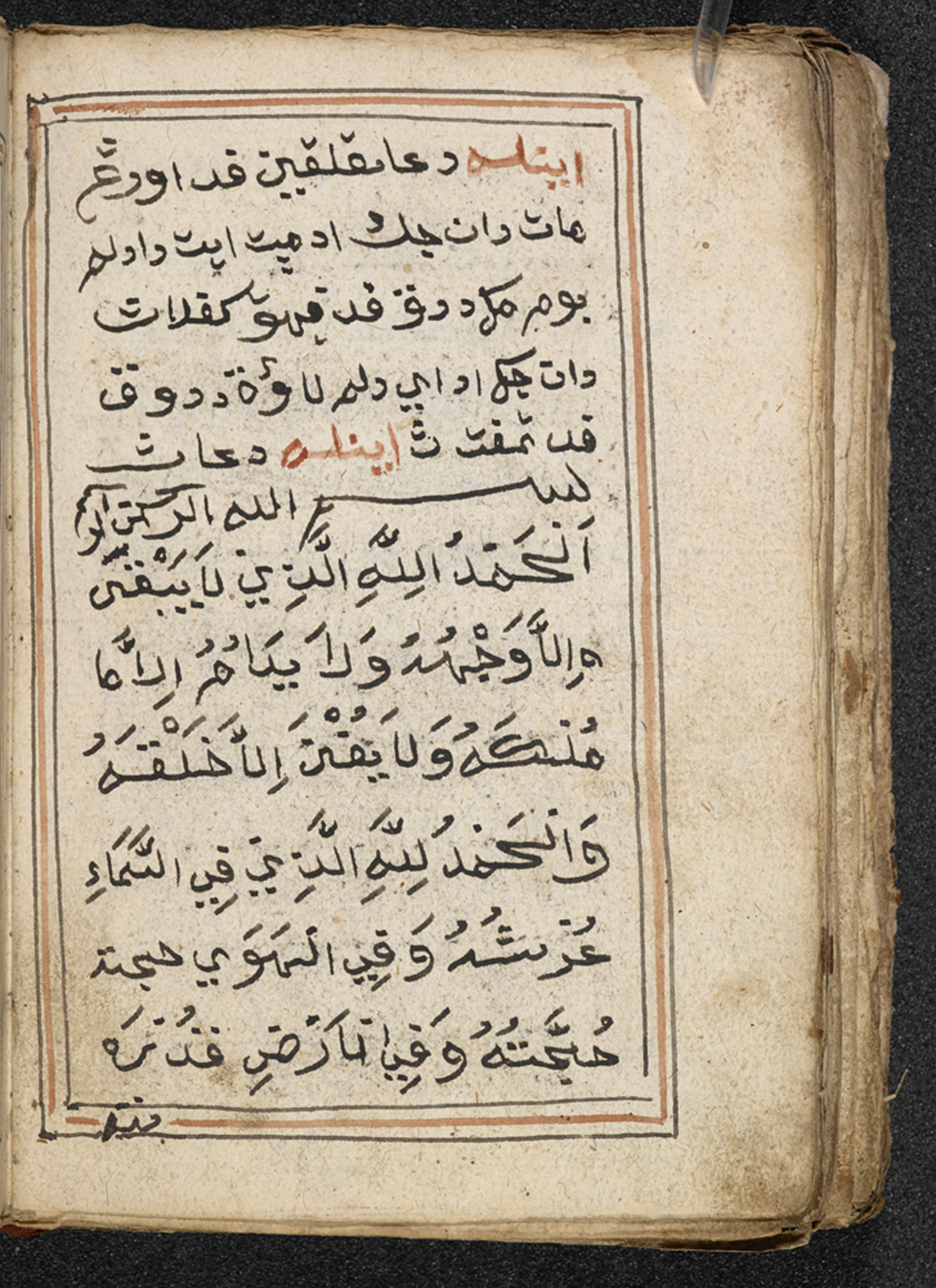

'Inilah doa talqin', prayer to be read for the dead, from a prayer-book from Aceh, Sumatra, 19th century. If the person is buried on land, then the reader of the prayer should sit by the head of the body, but if the person has died at sea, the prayer can be recited at an appropriate location (photo: British Library).

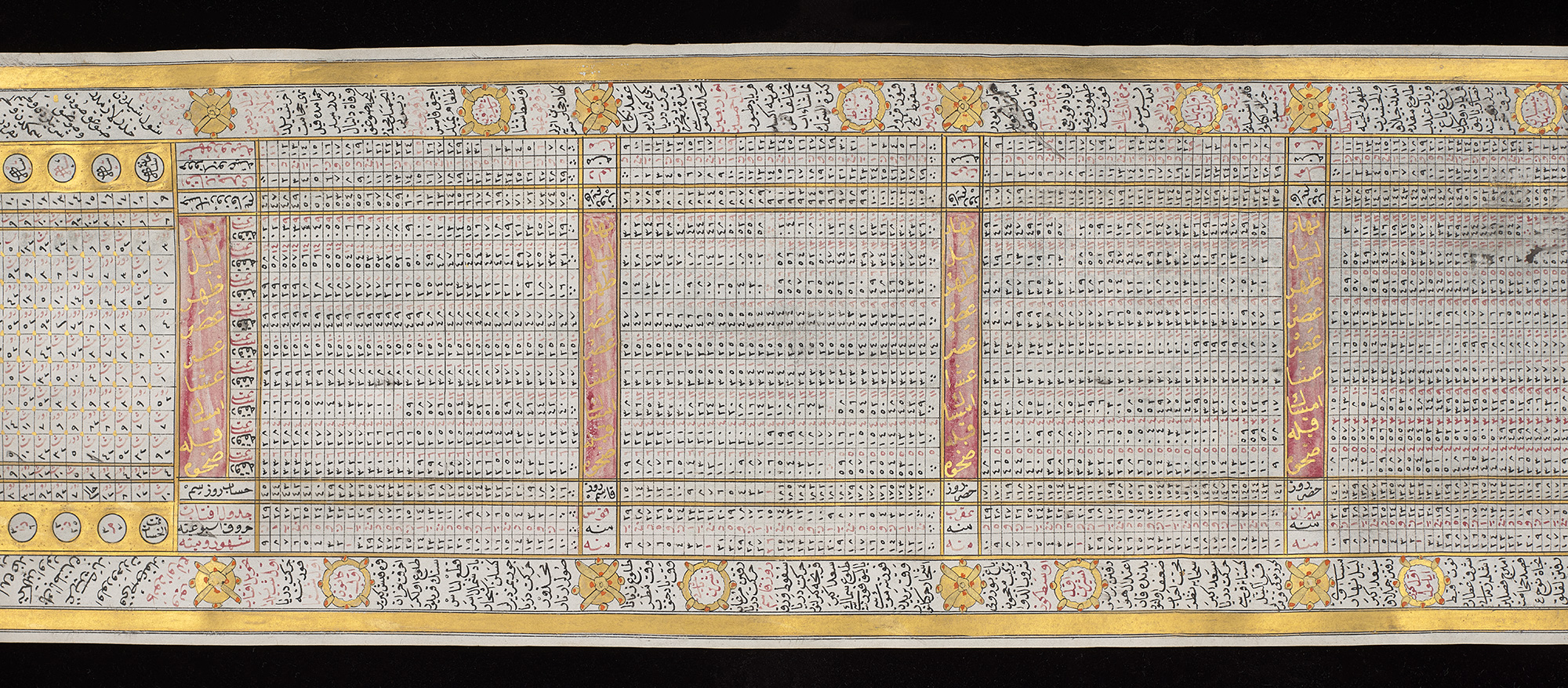

The Ruzname was probably produced in Istanbul, modern-day Turkey, in the mid-19th century. It is an almanac for the Hijri year 1225 (1810-11) and includes information about prayer times for each day of the year for the Istanbul region; the days and months of the Islamic calendar; and astrological information. It was created later than the year it refers to, and was probably intended as a souvenir rather than an actual calendar (photo: British Library).

The Haram at Mecca with the Kaʻbah in the centre, from a manuscript of Futūḥ al-Ḥaramayn, a poetical description of the holy shrines of Mecca and Medina and the rites of pilgrimage by Muḥyī Lārī (photo: British Library).

All purpose-built mosques are therefore built facing the direction of Mecca with a niche (mihrab) indicating the direction of the qiblah. In the event that Muslims must perform their ritual prayers elsewhere, they use their prayer rugs in order to assure that they are praying in a clean area. In these cases they have to estimate the direction of the qiblah. Nowadays, Muslims may use a prayer compass or a qiblah app to do this. Historically, detailed qiblah tables were found published alongside works on cosmology.

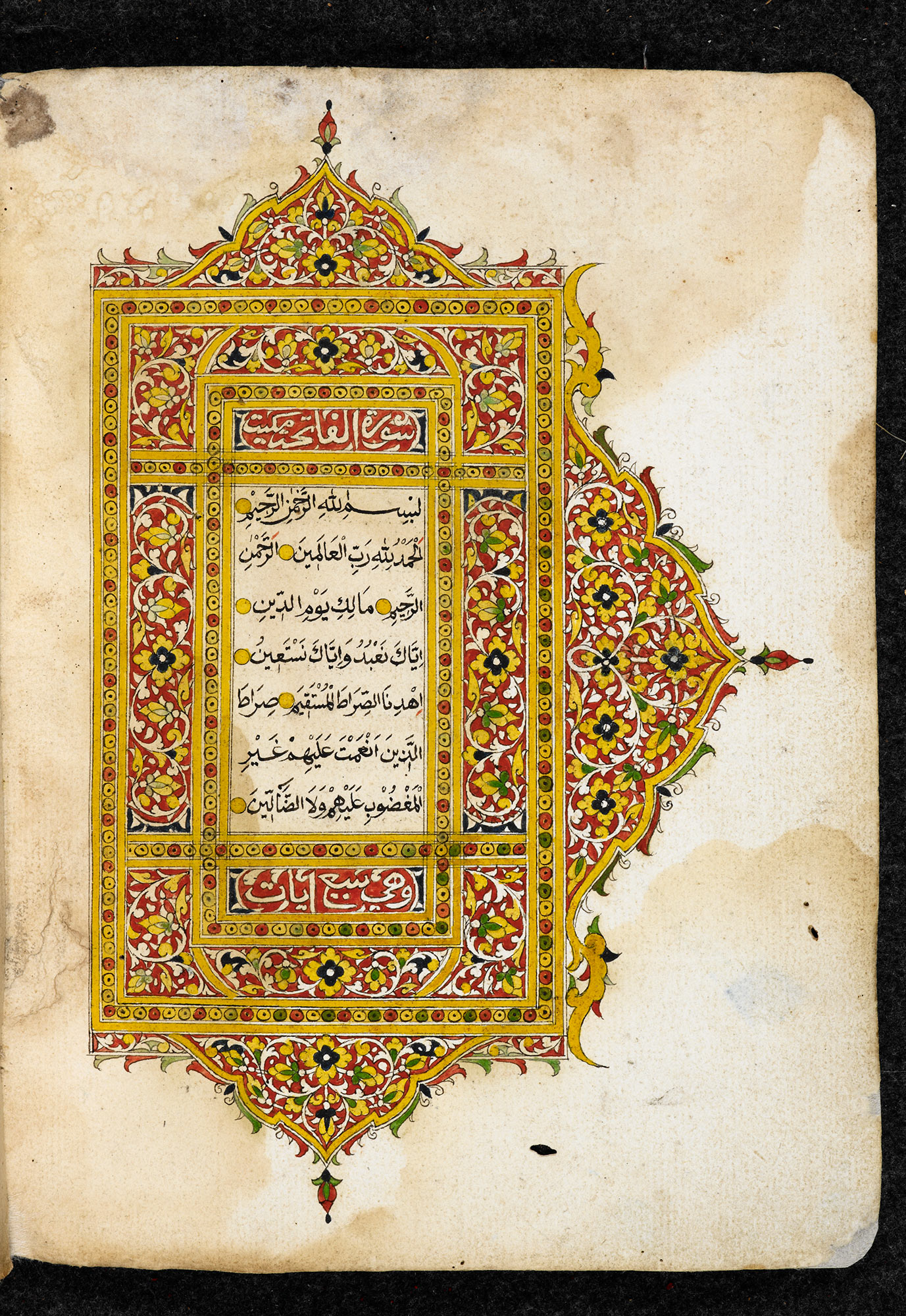

19th-century Qur'an from the East Coast of the Malay Peninsula (photo: British Library).

This is followed by further words of praise to God, the recitation of al-Fatihah (the first chapter of the Qur'an) and another section of her or his choice from the Qur'an. The rest of the prayer is concluded with various prescribed movements such as bows, prostrations and sitting. The whole ritual prayer ends with the worshipper first turning his head to the right and then to the left, saying 'peace be upon you and the mercy of God'.

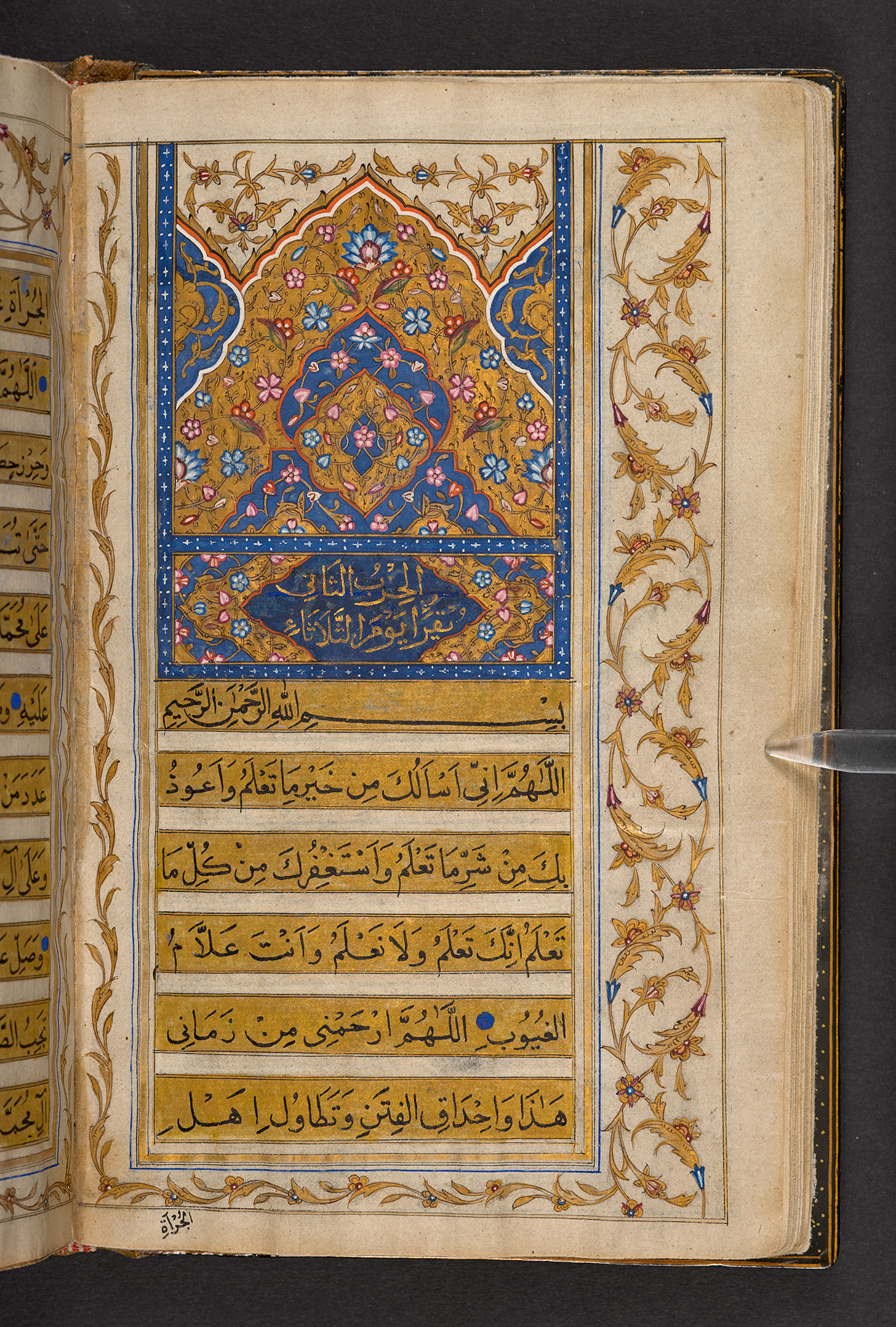

A devotional prayer-book, Dala'il al-khayrat (Guide to Goodness), a compilation of blessings on the Prophet. Featured here are prayers to be recited on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, respectively (photo: British Library).

The Dala'il al-khayrat ('Guide to Goodness') is a compilation of such prayers and litanies of peace and blessings upon the Prophet. Other works such as the book Mawlid sharaf al-anam('The Birth of the Noblest of Mankind') celebrate the nativity of the Prophet Muhammad and praise him as the final Messenger of God.

Amjad M. Hussain is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey. Previous to this post, Hussain worked as a Lecturer in Religious Studies at Trinity University College, Carmarthen and later as a Senior Lecturer in Islamic Studies at Trinity Saint David, University of Wales. His published works include, A Social History of Education in the Muslim World: From the Prophetic Era to Ottoman Times (2013), The Study of Religions: An Introduction (2015), The Muslim Creed: A Contemporary Theological Study (2016) and Islam for New Muslims: An Educational Guide (2018).