New questions about worship with spread of the Muslim world

The difference between the Muslim holy calendar and the Gregorian one not only makes the Ramadan fast a bit difficult at times. It also raises questions about how literally scripture should be taken.

Fasting during the summer heat is just one of the challenges faced by observant Muslims due to their rituals’ celestial ties, challenges that have increased as adherents of Islam have spread to every corner of the globe.

In most parts of the world, the holy month of Ramadan is marked by fasting from sunrise to sunset. This, however, is no easy dictate to follow in the northern longitudes, where, depending on the season, an entire day can be bathed in light or blanketed in darkness. The provisions made to help Muslims at the ends of the earth meet their religious obligations have sparked broader debate about how literally or figuratively core scriptures can be taken.

Though even most non-Muslims have likely heard about Ramadan and the practice of fasting, the details behind this debate may require a bit of explanation. Unlike the month of August or September, the month of Ramadan moves throughout the year, according to the lunar calendar, which is 10 days shorter than the Gregorian one that is now globally used.

The result is that Ramadan, along with the other 12 months of the Muslim calendar, comes 10 days earlier each year. So, in a given decade, the month of fasting can fall during in winter, summer, fall or spring. This year, it will start Wednesday and end Sept. 8. Next year, it will fill the whole month of August. Muslims in the northern hemisphere are thus in for a dehydrating decade of abstaining from food or water for the long hot summer days.

Between two poles

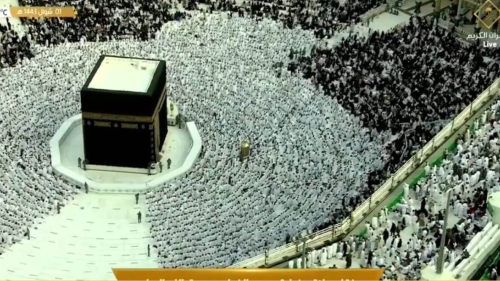

Throughout the centuries, Muslims became used to these fluctuations of Ramadan. In the past, most of them lived in what is traditionally called the “Islamic world,” an area that is, geographically speaking, quite extensive in terms of latitude (from Morocco to Indonesia), but not so much in longitude (from the Caucasus to North Africa). Hence, this part of the globe experiences days that have a clear beginning and end, and enough time in between to recuperate from the thirst and hunger of a fasting day.

All that became more complicated when Muslims started to live in places that are in or close to the Arctic and Antarctic circles. Even in, say, St. Petersburg, Russia, days in summer get close to almost 24 hours long during the famous “white nights.” Further north, in the polar circle, a “day,” technically speaking, lasts for months. That makes fasting impossible, if one stays strictly literal about the Muslim scripture and the way it measures time.

This issue of Muslims living at extreme longitudes has raised questions about not just the Ramadan fast but also the daily prayers, which are supposed to take place at five clearly defined times, all based on the sun’s movement: Morning prayer is just before sunrise, for example, while the noon prayer is held when the sun is at its highest and the evening prayer is made right after sunset. But, again, how can a Muslim follow this schedule if he or she happens to be, say, an Eskimo in Greenland or a scientist working near the South Pole?

Figurative time, figurative text

These questions did not occur to Muslims or anyone else until modern times – there was simply no need for an answer. In the 20th century, though, what has become a common question – “How is prayer and fasting possible at the poles?” – has been commonly answered by saying that in those parts of the globe, Muslims could simply fast and pray based on “Mecca time,” or on the time in their original homelands.

This practical solution has raised other questions, however. If the Quranic way of measuring time is not globally applicable, what does this mean for the nature of the scripture itself? Is its every single word literally relevant and applicable to all times and societies, as literalist Muslims typically argue? Or had the divine spoken through the context of the society that it was revealed unto – 7th century Arabia – as the proponents of a more figurative interpretation would say?

Both of these approach to the Quran – literalist versus figurative – have been present since the very initial centuries of Islam. One relevant theological debate that divided the early Muslim community was whether the Quran was “created” or “uncreated.” For the “uncreated Quran” party, the Muslim scripture had existed with God since eternity; it preceded the society and the events it referred to. The “created Quran” view, however, defined the scripture as the word that God spoke at a certain point in history, and partly in response to that historical situation.

Global scripture

“The wording of the Quran is local, but its message is universal,” argues İhsan Eliaçık, a popular Turkish theologian who defends the latter view. He thinks that God used the language and the concepts of 7th century Arabia to deliver a message with everlasting lessons. “Taking Quranic verses literally, by totally overlooking the cultural context that they were appealing to, would be misleading,” he said.

Take, for example, the Quranic verse that orders Muslims to arm themselves “with all the cavalry and infantry you can muster” to keep their enemies at bay. “Cavalry” is clearly only helpful in pre-modern warfare, so it is no wonder no Muslim military today takes that verse literally. But the meaning of the verse – that a strong military might help deter enemies – is still valid.

So can the verses about measuring time also be taken not literally, but figuratively? Can the time of the Ramadan fast be redefined, for example, according the realities of modern life?

So far, in mainstream Islam, only the “prayer at the poles” example has led to a reinterpretation – a very limited one.

The boldest step has come from the unorthodox Nation of Islam, a U.S.-based group of black Muslims, who long fixed the fasting month to December, when the days are shortest. (They changed that practice in 1998, to join the global Muslim community.) The Nation of Islam also has mosques with seats, resembling the churches in America. The common Muslim mosque style, after all, one can approvingly say, reflects Middle Eastern traditions, not divinely ordained rules.

Science or bare eyes?

On the other side, the literalist way, no one can be stricter than Saudi Arabia. Their adherence to classical methods to mark the beginning of Ramadan have led to disputes between them and other religious authorities, such as the official Directorate of Religious Affairs of Turkey along with religious institutions in Malaysia, Indonesia and some other countries that rely on calculations of the moon’s movement to determine exactly when the holy month begins, whereas Saudi Arabia and many other Arab Muslims insist that the moon should be “sighted” with bare eyes, as was done during the time of the Prophet.

As Muslims become even more global, and more integrated into modern life, these disputes will probably expand and the literalist way will become harder and harder to follow. That, perhaps, will be the key to the much-sought “reform” in Islam.

Topics: Fasting (Sawm), Prayers (Salah) Channel: Ramadan

Views: 1925

Related Suggestions