Masjid al-Haram Expansion: Acceptance or Criticism?

As part of their latest expansion of al-Masjid al-Haram (the Holy Mosque), the Saudis are criticized for speedy and insensitive destruction of Muslim historical sites and architectural heritage, without taking into consideration the feelings and views of professionals, experts and even ordinary people.

Their decisions and actions are seen as somewhat impetuous, arbitrary and one-sided, rather than additionally measured, punctilious and collaborative.

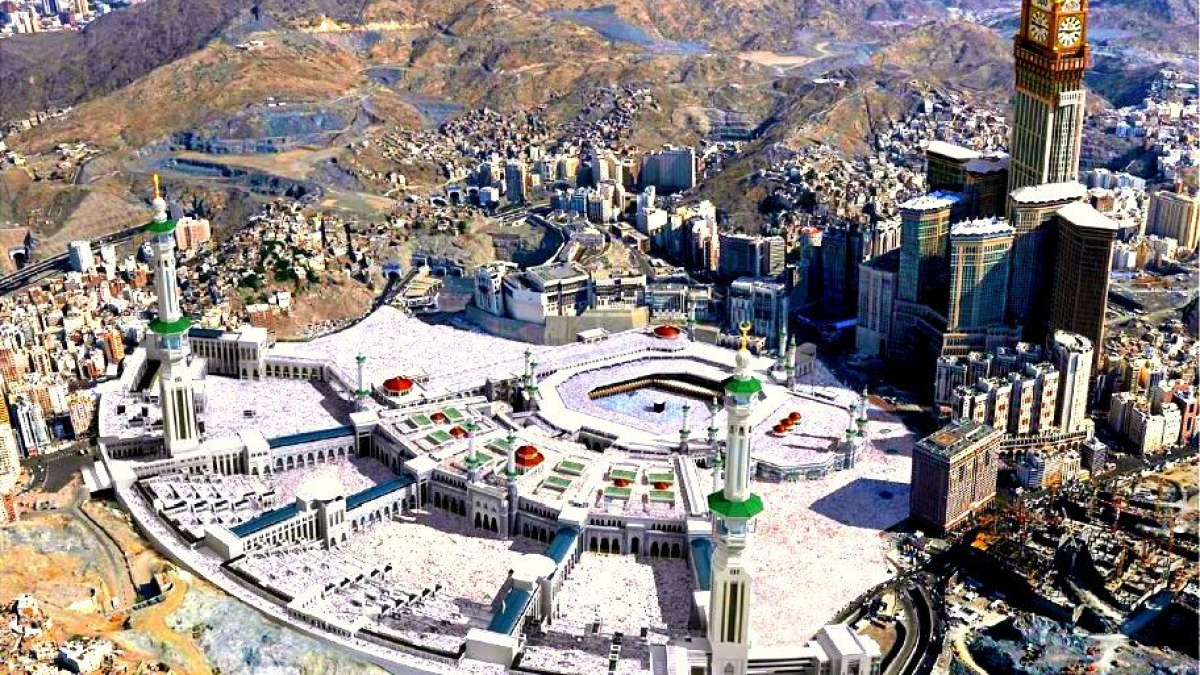

Most of the prevailing criticism comes from outside the country and varies from placid and constructive, to callous and derogative. Some of the harshest comments made were those to the effect that Makkah was robbed of its history; that the city was turned into a Makkah-Hattan or a Disneyland; that the city has become anti-historical giving preference to an ultra-modern, materialistic and consumerism predilection and culture instead; that it was increasingly catering to the needs of the super-rich at the expense of the average Muslims; and that as a result of the brisk development of the hospitality industry, services and facilities abutting the Mosque, the Ka’bah takes no longer central stage in the urban pattern and composition of the city.

Ziauddin Sardar went so far as to declare that “the dominant architectural site in the city is not the Sacred Mosque, where the Ka’bah, the symbolic focus of Muslims everywhere, is. It is the obnoxious Makkah Royal Clock Tower hotel, which, at 1,972 feet, is among the world’s tallest buildings. It is part of a mammoth development of skyscrapers that includes luxury shopping malls and hotels catering to the superrich. The skyline is no longer dominated by the rugged outline of encircling peaks. Ancient mountains have been flattened. The city is now surrounded by the brutalism of rectangular steel and concrete structures — an amalgam of Disneyland and Las Vegas… The few remaining buildings and sites of religious and cultural significance were erased more recently. The Makkah Royal Clock Tower, completed in 2012, was built on the graves of an estimated 400 sites of cultural and historical significance, including the city’s few remaining millennium-old buildings. Bulldozers arrived in the middle of the night, displacing families that had lived there for centuries. The complex stands on top of Ajyad Fortress, built around 1780 CE, to protect Makkah from bandits and invaders. The house of Khadijah, the first wife of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), has been turned into a block of toilets. The Makkah Hilton is built over the house of Abu Bakr, the closest companion of the prophet and the first caliph… Makkah is a microcosm of the Muslim world. What happens to and in the city has a profound effect on Muslims everywhere. The spiritual heart of Islam is an ultramodern, monolithic enclave, where difference is not tolerated, history has no meaning, and consumerism is paramount. It is hardly surprising then that literalism, and the murderous interpretations of Islam associated with it, have become so dominant in Muslim lands” (www.nytimes.com/2014/10/01/opinion/the-destruction-of-mecca.html)

It is difficult to say whether the mentioned and other similar judgments and accusations were sincere, productive and feasible, or signified no more than some old clichés, sentimental flare-ups, or even certain politically inspired sound bites.

Nonetheless, it is an endless debate whether and how much traditional neighborhoods with their traditional landmarks should give way to the colossal Mosque developments and expansions; or if they cannot be left alone, preserved and maintained, how far they should be assimilated into new modern architectural development schemes and designs, which will function as amalgams of the past and present, of tradition and modernity, and of intrinsic sentimental values and pressing present-day pragmatism and future visions.

Be that as it may, modernity, in the sense of being modern, contemporary and up-to-date, must move on and take its natural course, absorbing tradition and determining in a world of dialectics the latter’s direction and fate. Hence, modernity and tradition are most enduring and at the same time inseparable terrestrial truths. Undeniably, the vitality and dynamism of human existence are sustained only by constant interplays between them.

According to that paradigm, too, al-Masjid al-Haram had to develop and expand as a response to the development and expansion of the Muslim community worldwide, which the Holy Mosque was meant to symbolize and serve. The Mosque’s development and expansions also meant that the Mosque’s own traditional nuances and dimensions, and the traditional nuances and dimensions of its adjacent sites, needed to be revisited from time to time and be significantly impinged upon.

Such, furthermore, was a part of sunnatullah (the rules and laws of the Creator according to which His creation unfolds and exists). Thus, the question was never if, but when and how, the growths and expansions of al-Masjid al-Haram will materialize. No wise or insightful person will in principle ever criticize the notion of the needed and justifiable Mosque development and expansion, for such an act would be tantamount to voicing an objection to some of the most fundamental laws and principles that govern human existence.

Those who are fond of criticizing the expansions, do so only because of their disagreements concerning the ways and systems in accordance with which the inevitable was happening.

However, one thing is certain: all parties agree on the verity that the best Mosque on earth deserves the best form and function in order to serve the best religion, Islam, and its best followers, Muslims, even though some people’s motives became eventually colored with emotions, personal preferences, elements of socio-cultural relativism, and even with some political agendas.

Genuine criticism and feelings of unhappiness revolve around the truth that Makkah as a sanctuary and a holy land with the holiest Mosque within its precincts needs to be a standard setter in a myriad of life aspects, including Islamic urbanism and Islamic built environment, taking into account how big and serious a role Islamic spirituality plays in determining and shaping their respective recognizable characters.

This is especially so nowadays because of the cultural and civilizational trials and tribulations to which the Muslim world is subjected. It is now more than ever that Muslims need a sense of guidance and leadership in all spheres of their cultural and civilizational presence, so, Makkah, blessed, exalted and divinely safeguarded as it everlastingly is, connotes an Islamic civilizational locus people inherently look up to. If people’s hearts are attached to it, as the Qur’an explicitly says (Ibrahim, 37), so are their minds, intellectualism and overall physical and metaphysical existence.

Makkah, furthermore, should translate its God-given qualities and features into its civilizational penchant. As a safe and peaceful city (al-balad al-amin), its built environment in particular must echo the spirit of safety, care and peace insofar as people, the environment and the city’s ecosystems are concerned.

That predicates that the city’s built environment should at all times be sustainable and both people and nature-friendly, as well as that the well-being of the city’s ecological domain and its extremely limited resources, and the well-being of its people, permanent dwellers and temporary visitors and pilgrims, are not in any way compromised.

In other words, people in their capacity as vicegerents on earth need to forge and cherish safe and peaceful relations with all segments of the web of creation. Doing otherwise denotes some serious spiritual and intellectual disorders with far-reaching corollaries, in that a person’s lack of peace and constructive engagements with the natural world and other people indicates the lack of peace and of valuable bonds with his own self and his Creator and Master.

That said, it must be reiterated, particularly in the context of the Islamic built environment - which is perceived, created and used as part of living a divinely inspired Islamic life paradigm, and which functions both as a catalyst and framework for Muslims’ fulfillment of their noble vicegerency (khilafah) mission - that Islam is a religion that aims to ascertain, uplift and sustain the honor and dignity of man because in Islam, man is God’s trustee on earth. Every terrestrial being has been created for the purpose of accommodating and facilitating the realization of man’s splendid mission.

Man resides in the center of Islam’s universe. Islam exists because of man; it is meant for him. Man, in turn, exists because of, and for, Islam, to be shown how to live in complete service to his Creator, and to be shown the way to self-realization and deliverance in both worlds.

It goes without saying that the ultimate objective of the Islamic message is the preservation of a believer and his honor and dignity. This translates itself into the preservation of his religion, life, lineage, intellect and property.

There is nothing on earth that is more inviolable than a believer: his blood, property and honor. There is nothing that supersedes him in importance. Everything on earth exists in order to make possible and then sustain a believer’s lofty position. All things and events play second fiddle to his status. Yet holy messengers were sent and revelations revealed for that very purpose.

Based on the divine Will and purpose, life systems, ordinances and practices are concocted for this same end as well. Accordingly, cultures and civilizations are judged only on the basis of how genuinely they were human honor and dignity-oriented and how much they succeeded in making such enterprise a reality.

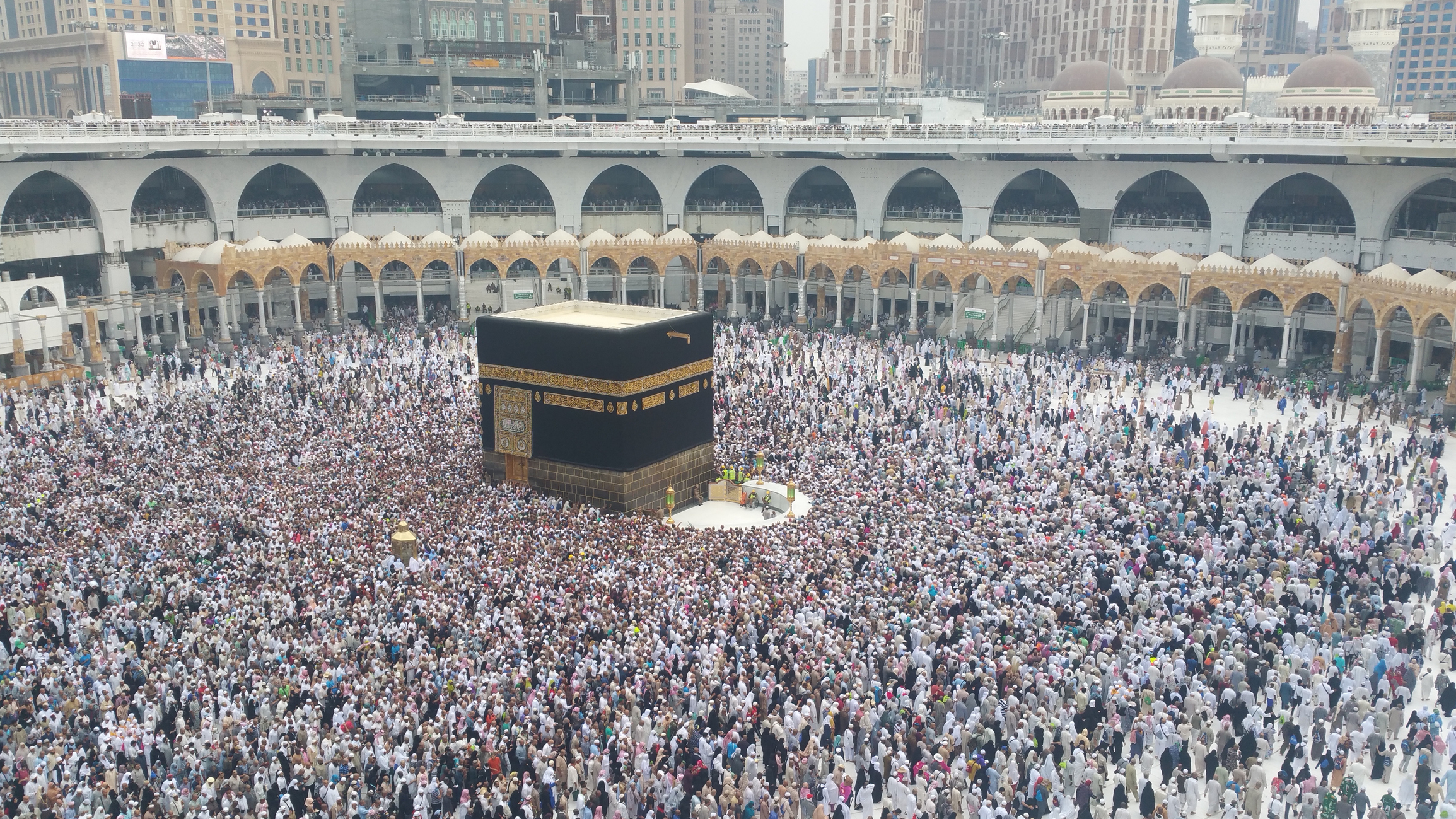

It was due to all this that the Prophet (pbuh) is reported to have communicated to the Ka’bah while circumambulating it (tawaf): “How pure you are! And how pure is your fragrance! How great you are! And how great is your sanctity! By Him in whose hands lies the soul of Muhammad, the sanctity of a believer is greater with Allah than yet your sanctity (i.e., the Ka’bah). That is (the sanctity) of his property, his blood and that we think nothing of him but good.”

A companion of the Prophet (pbuh), ‘Abdullah b. ‘Umar, once when he looked at the Ka’bah, reproduced the gist of those Prophet’s words and said to the Ka’bah: “How great you are! And how great is your sanctity! But the sanctity of a believer is greater with Allah than yet your sanctity (i.e., the Ka’bah).”

The Prophet (pbuh) also said during his farewell pilgrimage in a sermon which denotes a blueprint for every Muslim civilizational awakening: “Verily, your blood, property and honor are sacred to one another (i.e., Muslims) like the sanctity of this day of yours (i.e., the day of Nahr or slaughtering of the animals of sacrifice), in this month of yours (the holy month of Dhul-Hijjah) and in this city of yours (the holy city of Makkah).”

Definitely, it was not by chance that in the above instances the notion of preserving Muslim sanctity, dignity and honor has been emphasized in the context of the city of Makkah and its two most important components: the Ka’bah (al-Masjid al-Haram) and the plains of ‘Arafat.

Hence, it is right in Makkah where the same notion ought to be incessantly demonstrated and upheld. For that reason was expanding al-Masjid al-Haram into the historic and traditional Makkah neighborhoods an opportunity to emphatically demonstrate that the authentic Islamic built environment is a realm where peaceful coexistence and relationships between people and their selves, between people and God, and between people and their natural environment is forged, where tradition and modernity are at ease and not locked in conflicts whereby one always makes an attempt to outstrip and repeal the other, and finally where the principal authority and point of reference is the worldview (Weltanschauung), teachings and ethical system of the Islamic message, instead of people’s individual predilections and transitory indigenous or global socio-economic trends.

In an ideal world, the whole process of the Holy Mosque’s expansion, involving relocation of people and demolition of what could not be preserved, coupled with introducing genuinely creative plans, designs and most up-to-date building technology and engineering, should serve as a qiblah or direction, so to speak, in the current Muslim architectural ambitions and goals.

Just as an immense, virtually endless, budget was generously assigned for financing the expansion, the same undertaking, similarly, needs to characterize a source of continuous architectural originality, sovereignty and vision, which will be able to leave a lasting effect not only on the Muslim community, but also on the world at large.

Al-Masjid al-Haram should function as a unifying factor for the Muslim ummah in the civilizational enterprises of theirs, just as it is their qiblah and unifying factor in their spiritual matters. Makkah thus ought to be transformed into a true “Mother of cities” (Umm al-qura) - as the Qur’an brands it (al-An’am, 92) - and to be truly and at all levels more venerated, inspiring and more guiding than other human settlements.

That all cities are to be subordinate to Makkah is a dignified goal towards which all Muslims should strive.

Some additional incentives for collectively trying to realize the above mission and purpose are as follows. The city of Makkah has been made a sanctuary and a holy place the day God created the heavens and the earth, and it will remain so by God’s command until the Day of Resurrection; committing sins in Makkah is immense, and doing good deeds procures manifold rewards; Makkah is a place of security and safety not only for humans, but also for all animate and inanimate beings; Makkah is the most beloved piece of the earth to God and, as such, to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) about which he said in the course of hijrah, or migration to Madinah, that if he had not been driven out of it, he would have never left it; the inability of Anti-Christ or Dajjal, and general impermissibility for non-Muslims, to enter Makkah, which symbolically could also be construed in terms of impermissibility of innovating Islamically unacceptable cultural and civilizational principles, standards and norms in Makkah, or importing the same into it from outside.

In any case, God purifies, protects and nurtures Makkah, but people, too, must do their part within their abilities and contexts. Accordingly, if aspects of old traditions and heritage had to go as a consequence of the inevitable and well-thought-out Mosque expansions, corresponding aspects of new traditions and legacies will be created thereby. They will be able to embody and radiate the quintessence of Islamic urbanism, planning, art and architecture as much as the former did. People will not then be talking about sudden breaks with the past, discontinuity and regression, but about smooth transitions, progress and evolution.

Only this way will justice be done to history and affected traditions, and will modern architectural genres go down well with most people and their Islamic cultural and civilizational benchmarks.

As a small digression, authentic Islamic architecture, in effect, is synonymous with man’s honorable vicegerency (khilafah) assignment on earth. An architect is a person who does his best to make life meaningful, easy and comfortable for people. An architect, furthermore, is a responsible custodian who must strive to prevent the uncontrolled use of natural resources.

In this manner, Islamic architecture is to be seen as a profession and discipline that embrace and advance the concept of moderation (wasatiyyah), echoing thereby the sum essence of the Islamic message. It is a pursuit of mutual giving and taking.

The soul of architecture is not entirely about tensions between luxury and poverty, pride and modesty, extravagance and prudence, modernity and tradition, construction and destruction, and so forth. The quintessence of architecture needs to transcend that somewhat superficial level and exist in a world of higher and more sophisticated interpretations and meanings.

Islamic architecture is about a thorough lifestyle that personifies the creed, teachings and ethos of Islam. It signifies translating the latter into the realm of life’s conceptual and tangible realities. Simply put, it is Islam incarnate.

The latest expansion of al-Masjid al-Haram divides opinion more than any other expansion did in the past. Experts’ as well as common people’s standpoints vary from out-and-out support to stern criticism of almost anything pertaining to the nature of the expansion. Between these two almost diametrically opposed to each other attitudes lies a wide range of points of view some of which tend to tilt towards one side of the divide while others do towards the other.

However, two things are evident. There is no one in the whole pattern who denounces the expansion per se and the needs that called for it; nor is there virtually anyone who is utterly indifferent to, or neutral in, the ongoing debates that are assuming, unsurprisingly, unprecedented proportions.

At any rate, the Holy Mosque expansion, including its scale and magnitude, is rather justifiable. However, more time and more sensitivity were required, and more conscientiousness and dialogue with diverse and worldwide experts, including the general public, were needed when it came to dealing with and ultimately destroying entire traditional neighborhoods and some other places of historic significance, which not only the local population, but also all Muslims, had huge stakes in.

This is in order that systematic and painstaking research, evaluation and documentation efforts could have been carried out by professionals and academics for the purpose of future education, recognition and appreciation of the country’s Islamic built heritage. Since its inception, the project should have been more participative and inclusive, rather than exclusive and controlled, more flexible and fluid, rather than rigid and unbendable, and more heterogeneous, multidimensional and diversified, rather than excessively and fixedly monolithic and homogeneous. Also, more urban planning and architectural creativity and resourcefulness were needed in an attempt to address more effectively various people’s concerns.

It must at the same time be conceded that, as to a great many aspects of all the contentious issues in the Holy Mosque expansion debate, there is extremely little that is definite right or wrong. There is a lot of gray area, along with the matter of personal emotions and preferences, and certain limited historical, cultural and socio-economic interests.

Thus, extreme caution, respect, restraint and a sense of moderation ought to be espoused by everyone involved. Such is the state of affairs of the expansion exercise that many people’s views and judgments may well amount to the ijtihad category, which is “the independent or original interpretation of problems not precisely covered by the Qur’an, Hadith (traditions concerning the Prophet’s life and utterances), and ijma’ (scholarly consensus).”

Ijtihad, therefore, is putting forth the maximum effort in a process of forming an independent opinion or judgment within the framework of available texts concerning a life activity. In doing so, if one excels, one receives two rewards from God, but if one for whatever reason, fails to deliver, after he had tried his best, he is bound to receive a single reward from God - as explained by the Prophet (pbuh) in one of his traditions.

Hence, if permeated with the spirit of true ijtihad, qualified people’s opinions matter and should always be listened to, respected and taken into account. In areas where ijtihad is due, there is no absolute right or wrong. Ethics of disagreement, mutual respect and cooperation for a greater cause are put on a pedestal.

Perhaps, a form of exhaustive collective ijtihad would have been a way forward as well, partially at least. The case of expanding the Holy Mosque (al-Masjid al-Haram) needs always to be used to unite, not divide, Muslims, and to procure universal goodness, rather than unhappiness and distress, for them.

For instance, there is vast disagreement among traditional and contemporary scholars alike as to what exactly is meant by al-Masjid al-Haram in one of the most well-known authentic hadiths of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) where the extraordinary spiritual significance of the Holy Mosque is revealed. The Prophet (pbuh) said: “One prayer in my Mosque (in Madinah) is better than one thousand prayers elsewhere, except al-Masjid al-Haram, and one prayer in al-Masjid al-Haram is better than one hundred thousand prayers elsewhere.”

There are several opinions with regard to what is meant by al-Masjid al-Haram wherein the reward for prayer is multiplied. The most prominent ones are: it is the Ka’bah; it is the Ka'bah and the mosque around it; it is the entire Haram (Makkah sanctuary) and ‘Arafah; it is the Ka’bah and what is within the Hijr or Hatim of the Ka’bah; it is Makkah; it is the entire Haram of the city of Makkah up to the boundaries that separate the outside world from the Haram; it applies to the place where it is forbidden for the person who is junub (ritually impure) to stay.

What’s more, while in Makkah performing the pilgrimage (Hajj), Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) is reported to have encamped at a place called al-Abtah, a few miles away from the Ka’bah and al-Masjid al-Haram towards Mina (a distant zone of Makkah). He did so in order that his Hajj rituals, which involved several holy sites outside the city of Makkah including Mina, were better facilitated, and “so that it might be easier for him to depart”.

The Prophet (pbuh) might have come to the Ka’bah and al-Masjid al-Haram only in order to perform those rituals which were directly and indirectly connected with them, such as tawaf (circumambulating the Ka’bah) and sa’y (walking and running between al-Safa and al-Marwah mounds). As such, the Prophet (pbuh) spent a large chunk of his time in Makkah as a pilgrim, and performed a number of his daily prayers, away from the Ka’bah and its Holy Mosque.

So, if people legitimately as a result of their ijtihad have different viewpoints on the subjects of the meaning and extent of al-Masjid al-Haram, it likewise is very likely that they will have different views about the ways the Mosque should be expanded and built, so as to accommodate as exorbitant a number of visitors and pilgrims as today’s estimations stand for the latest expansion – and that should be duly respected and taken in everybody’s stride.

For some people, for instance, if the scope of the Mosque is the entire city of Makkah, or the boundaries of its sanctuary (haram), the notions of enlargement and expansion should then not concentrate on the immediate vicinity of the Ka’bah only, and so, wipe out the physical residues of its centuries-old history and heritage. Rather, planning and construction activities should be wisely and evenly distributed across the distant perimeters of the Mosque as the city’s sanctuary (haram) with the aim of elevating severe strains from the heart and focal point of the city.

Others, on the other hand, also legitimately as a result of their own ijtihad, would beg to differ with the former perspective’s proponents, putting forth their own arguments which are neither more nor less convincing than those of the first group.

In any case, nobody is to try to monopolize the debate, believing that only he and his camp are right, and everyone else wrong. Instead, the matter could – and should – be used for forging a greater good for the Muslim ummah. Differences of opinion are there to stay and are to be respected and amicably dealt with.

Matters pertaining to sheer ijtihad are meant to energize Muslims and broaden their spiritual and intellectual horizons. They are not to divide them, nor undermine and fritter away their motivation and capacities.

(The article is an excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book titled “Appreciating the Architecture of Shamiyyah”)

Topics: Islamic Art And Architecture, Islamic Culture And Civilization, Makkah (Mecca), Masjid Al Haram

Views: 23960

Related Suggestions