The Sources of Identity in the Islamic Diaspora

Motion, Movement and Migration

Of the many perspectives on African social development is the so-called modernizing theory, one of the foundations of the social sciences in the mid-twentieth century. The modernization theory was as popular in African studies then, as cultural studies or multiculturalism by the early 1990s. Before the colonial era in Africa, the uniqueness of Africanity, which included the prowess of collective kinship or ethnicity, replaced the lack of state formations traditionally built upon economic stability, military security, and culture. With a plethora of African ethnicities existing before the colonial period, and in spite of cases of exaggerated and imagined bases to that ethnicity, consciousness developed. In Africa, a network of ethnic loyalties existed because of ethnic consciousness, all designed for the benefit of group inclusion, and to the exclusion of other forms of edifying expressions. What inspired these formations became the seminal moments in the success African American Muslim organizations experienced centuries later in the African Diaspora.

In the Islamic Diaspora, an unprecedented historical experience unfolded based upon the Diaspora of Enslavement. The European slave trade recon-figured African continental kinship dynamics and refocused the paradigm in the African Diaspora from ethnic consciousness to racial consciousness.

For the masses of captives, enslavement drove many religious, cultural, and ethnic practices into unfamiliarity. However, with the organic cultural synthesis formed in the face of enslavement, African Muslim kinship specifically and kinship throughout the African Diaspora generally, was necessitated and employed in entirely different fashions. Within the Diaspora of Enslavement, the idea of ethnicity grew subtle and less significant while inclusion into the Kinship of the African Diaspora revolved around race consciousness. However, subordination in captivity inspired Africa's Muslims to construct a primordial consciousness based upon three historic interventions. Although notions of African ethnicity were discouraged in the west, African Muslims' closely held Islamic principles superseded race consciousness.

The three historic interventions taken from the Qur'an are motion, social movement, and migration. These three transcendent concepts continue to shape the face of Islam in post-modernity, while greatly influencing the social landscape in which Muslims operate in the United States, Caribbean, and South America. West African Islamic pedagogy, based upon the elucidation of the Qur'an and the practices of the Prophet Muhammad, sallallahu alayhe wa sallam, are the inspirational sources for millions of Muslims of color. In spite of this, the two theological sources of Islam are not the Qur'an and the Sunnah. The saga of the African Diaspora for descendants of African Muslims is the story of the three concepts fused by how kinship unfolded in the African American community. Although Islamic religious sentiment can be trace from early America through to post-modernity, the internal kinship produced in the Islamic Diaspora has not served the minority political polity or been a point of reconciliation within the broader African American community.

Since the first institution in Islam is the Salah or prayer, the first obligation to God is satisfied through motion.

The Qur'an details the origin of salah in the story of the "Night-Journey and Ascension" or Al-Israa wal-Mi'raj. In one night, the Prophet Muhammad, sallallahu alayhe wa sallam, was physically transported from Makkah to Jerusalem and from there to the highest stages of Heaven. Muhammad then commanded Muslims to establish five daily salah or prayers performed in the manner seen in post-modernity. Solemnity and serenity in prayer predicate the world's religions in spite of this the motion during the Islamic prayer is considered a rigorous spiritual activity. Regardless of race, class, language or geography, Muslims find a sense of identity based upon collective motion in salah.

The second Islamic historical feature is migration.

The Great Muslim migration of the early seventh century, the move to escape religious persecution, was the beginning of Islamic history. Tawheed or monotheism and salah created this small but dedicated Arab community in Makkah. Muslims forced to flee from one oppressive location in Makkah to a more hospitable one in Madinah led to the seminal moments of one of the world's greatest social movements.

In the face of discrimination, racism, cultural negation and personal safety, Islam strongly encourages migration. Allah says in the Qur'an, "have I not made the entire earth a place of prayer and refuge" [4:97]. Ali Mazrui reminds us that Islam, as op-posed to Hinduism, was not "intended to be a religion of the transmigration of the soul but of the movement of the body and the migration of the person."

When considering the beginning of the Islamic era, and the birth of the calendar, the global community once again embraced migration. The Islamic era did not begin with the birth of the Prophet Muhammad, sallallahu alayhe wa sallam, in 578, his death in 632, or when in 610 he became prophet. The migration in 622 inaugurated the Islamic era. The history of Muslims moving to the western hemisphere is a fascinating account of modern migration.

The third Islamic historical feature is social movements.

The record of mass Muslim movements in the African Diaspora began in Trinidad in 1770 with Man dingoes brought to Port of Spain from Senegal. Of this movement, Omar H. Kasule wrote, "In the 1830's, a com-munity of Mandingo Muslims who had been captured from Senegal lived in Port of Spain. They were literate in Arabic and organized themselves under a forceful leader named Muhammad Beth, who had purchased his freedom from slavery. They kept their Islamic identity and always yearned to go back to Africa."

As early as the eighteenth century, the African Diaspora contained Muslim communities not necessarily relying upon theological underpinnings but theism based upon an Islamic identity forced to accommodate captivity. In July 1990 members of a radicalized Trinidadian group known as the Jamaat al-Muslimeen seized the Parliament and held Prime Minister A.N. R. Robinson hostage. Trinidadian Muslims indicated they traced their lineage to enslaved Mandingo Muslims. The protestors demanded public recognition of the Muslim community, apologies for centuries of captivity, business opportunities and economic enfranchisement. Although many demands for social reform were never realized, the demonstrators received asylum and the government never prosecuted them. Along with the Million-Man March, the seizure of the Trinidadian government marked the most dramatic and visible act ever perpetuated from the African Diaspora. Unfortunately, this demonstration was inspired by a highly contested interpretation of Islam's concern for social justice.

Religious Paradigm Shift in the Diaspora of Colonialism

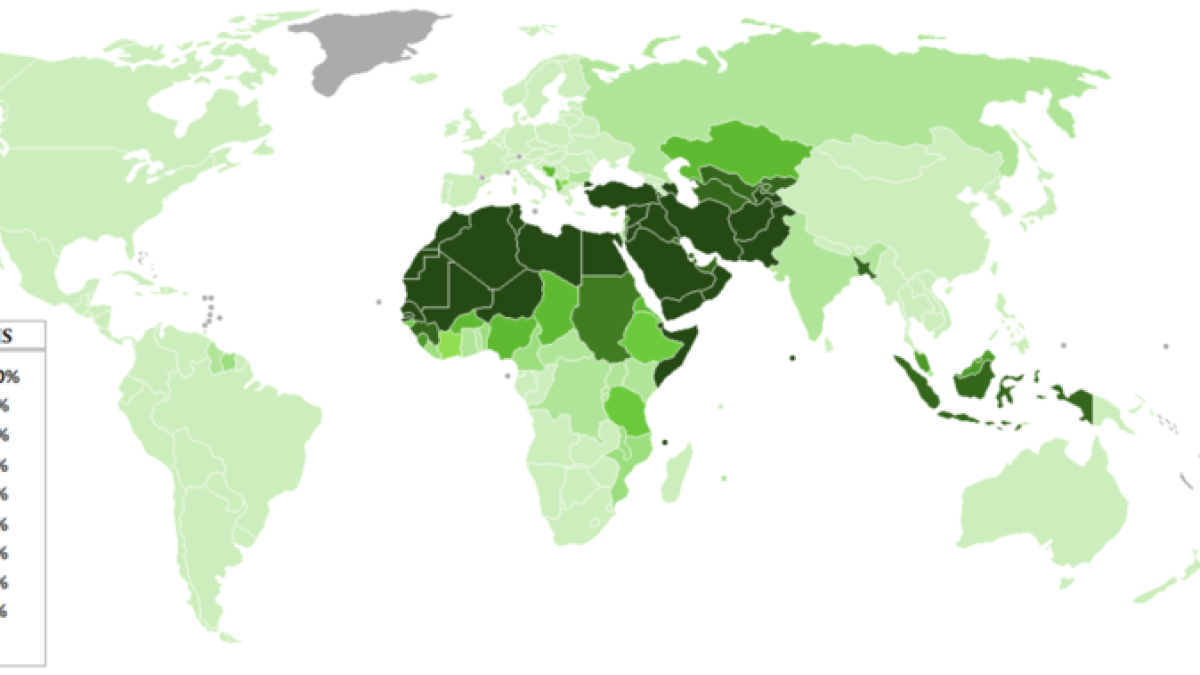

The Diaspora of Enslavement shaped the image and theology of the proto-Islamic groups formed between 1915 and 1970. On the other hand the theology of the orthodox Sunni Islamic community was inherited from Islamic classicists of the Levant. With unprecedented migration by the 1980s, and the interaction between the soon to be dethroned African American Muslim community and the immigrant Muslim, we see the spread of Islamic theology from primarily Indio-Pakistani and Arab Muslims.

With the import of various cultures migrating from under the yoke of the colonial chain, Islamic theology unintentionally became a point of contention in the newly shaped Diaspora of Colonialism. Although tension resulted from a clash of imported cultures and indigenous American perspectives, the durability of the three dynamics remained. The religious interaction between the two formed the Diaspora of Colonialism, a direct result of decolonization and voluntary migration. In the after math in the United States, primarily Arab, Pakistani and Indian nationalism gave birth to small theological and cultural fiefdoms.

Decolonization and independence in Muslim countries affected the formation and growth of the 1990s orthodox Salafi, Shia and "Muslims of the Americas" communities. After the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975, W.D. Muhammad inherited his father's leadership role and the movement gravitated towards the orthodox Islamic persuasion. Louis Farrakhan's Nation of Islam (NOI) (although in the twenty-first century it has leveled off in numbers) remains, again, through kinship, black nationalism's most audible voice operating with little regard for the three historical concepts discussed here.

Islamic Kinship and the 20th Century

|

Noble Drew Ali was the first African American Muslim in modernity to borrow from the three concepts and exploit race consciousness, the backbone of African collectivity, pride and security. By the turn of the 20th century, as life breathed into the bigoted body of Jim Crow, it was clear America would never abdicate its throne of white superiority. The engraved lines of racial demarcation in the United States, reminiscent of ancient threats from stronger African villages, was an opportunity for Ali to galvanize and manage racial consciousness into a broad-based platform for group inclusion and pride.

In 1915, he opened the Moorish Science Temple (MST), the first African American proto-Islamic organization in America. Ali and his followers believed the black man originated in North Africa, probably Morocco. Known as the Maghribis, their history recounts reports of the original black man captured from ancient Sub-Saharan villages and herded north to Morocco. Like many in the "return to Africa movement," the MST relied upon new forms of kinship. Although not as visible today as its presence in the mid-twentieth century, the organization is theologically unrecognizable in the Muslim world. Ali's Muslims were intimately connected to the three Islamic concepts; nevertheless, what distinguished the MST was also their assertive black nationalist rhetoric.

In 1930, Elijah Muhammad, amidst the Great Migration, inherited the mantle of religious authority from Master Fard Muhammad, a Turk or Pakistani who claimed to be God incarnate. With less than a sixth grade education, Elijah Muhammad used the power of prayer to a black God, and the history behind the forced migration of Africans, to create the most powerful religious organization in the African Diaspora and social movement outside the African American church. With one part black nationalism, one part economic empowerment and the other part proto-Islamic doctrine, the Nation of Islam dominated the Islamic landscape until the late nineteen sixties.

With the acumen and acuity of ancient African leadership, Muhammad realized the maligned image of racist and segregated American state authority did not convey a sense of pride, security or patriotism in African Americans. Muhammad, like the proficiency of ethnicity in ancient Africa, utilized racial consciousness instead of parochial ethnicity. As the Great Migration north was in full swing Muhammad, like Ali, leaned on primordial consciousness to capture and direct a following of people finding satisfaction in a sense of group kinship.

Theologically Elijah Muhammad's interpretation of the Qur'an located the NOI well outside classical Islam, nonetheless by placing value on the dignity of the black man, Elijah Muhammad built a self-sufficient community on reinvigorated kinship, one that has not been duplicated by people of color since the Songhay Empire. The NOI, although maligned in a skeptical Christian society, because of a distinctive brand of kinship remained the dominant Islamic player from the nineteen fifties until the immigrant explosion of the 1990s.

The emergence of the orthodox Muslim community in the nineteen sixties, although connected to a longer line of Islamic kinship, never threatened the market share maintained by the NOI. In the proto-Islamic and black nationalist communities, Islamic orthodoxy was detested because of its Arab cultural veneer. They criticized classical Islam as being uninformed of the African American condition and intolerant of African American culture. Salient black nationalist sensibilities within the NOI rejected classical Islam and the orthodox African America Muslim. They contend that beginning with in the eight century Arabs have remained interlopers in Africa, culturally hegemonic and ethnically insensitive to Africanity.

There are consistent and inconsistent patterns amongst Muslims of African descent in the western hemisphere. Beginning with agreement on the sacredness and wording of the Qur'an, Muslims differ on the practices of the last Prophet Muhammad, sallal-laliu alayhe wa sallam. There is accord on some prophetic traditions and the necessity of individual and collective salah, but there is no unanimous agreement on how to perform the salah. In spite of such cultural dissimilarities and theological incongruities, Islamic kinship prevails. Historically cultural diversity was the efficacy of the Islamic legacy, nevertheless in post-modernity, Islamic kinship revolving around the three fundamental concepts has not become a point of religious contention. Muslims of color are not historically dependent. In this regard, identity is not traced to how history is read but what motion, movement and migration mean to the contemporary Muslim.

Nonetheless the contemporary Muslim community, despite the irony of reading the same text, on a daily basis performing the same salah ritual, and experiencing in some fashion the impact of migration, has failed miserably to initiate any significant collective social movement involving the national American Muslim community.

The subtle but significant link between traditional Islam as motion, movement and migration and modernized Muslim because of motion is a significant contemporary distinction for the identity of Muslims occupying the African Diaspora. The lack of discourse between the two groups is indicative of the future perils of a divisive community with no agreed upon agenda. Patented self-conceptions and group impressions will determine new social challenges based upon new cultural identities as a means of understanding the state of the Islamic African Diaspora.

*****

Article provided by Al Jumuah Magazine, a monthly Muslim lifestyle publication, which addresses the religious concerns of Muslim families across the world.

To subscribe please visit https://www.aljumuah.com/subscription