Sufism

This article explores Sufism, Islamic mysticism. It charts its development as a historical phenomenon, its terminology and literature, as well as delving into the aim of the Sufi spiritual path and the importance of spiritual masters and the Qur’an.

What is Sufism?

Sufism has been defined in different ways by scholars of Islam, both from within the Muslim tradition and from outside of it. The debate on the nature, reality and essence of Sufism reflects the plurality of ways in which Sufism has manifested itself historically and geographically, resulting in a plethora of forms that sometimes bear little resemblance to one another. Often defined as the mystical or esoteric strand of Islam, Sufism’s defining feature is the centrality of the individual’s direct relationship with God. The individual devotee strives towards establishing a direct, inner connection with God, or the acquisition of a transformative knowledge of the Divine. Another way the Sufis have often described the inner experience of the Divine is through the symbolism of the veil: because the inner reality of human life is nothing but God itself, true self-knowledge amounts to the knowledge of God, which can be attained by removing the veils that cover a human being’s true nature and prevent them from seeing God within themselves.

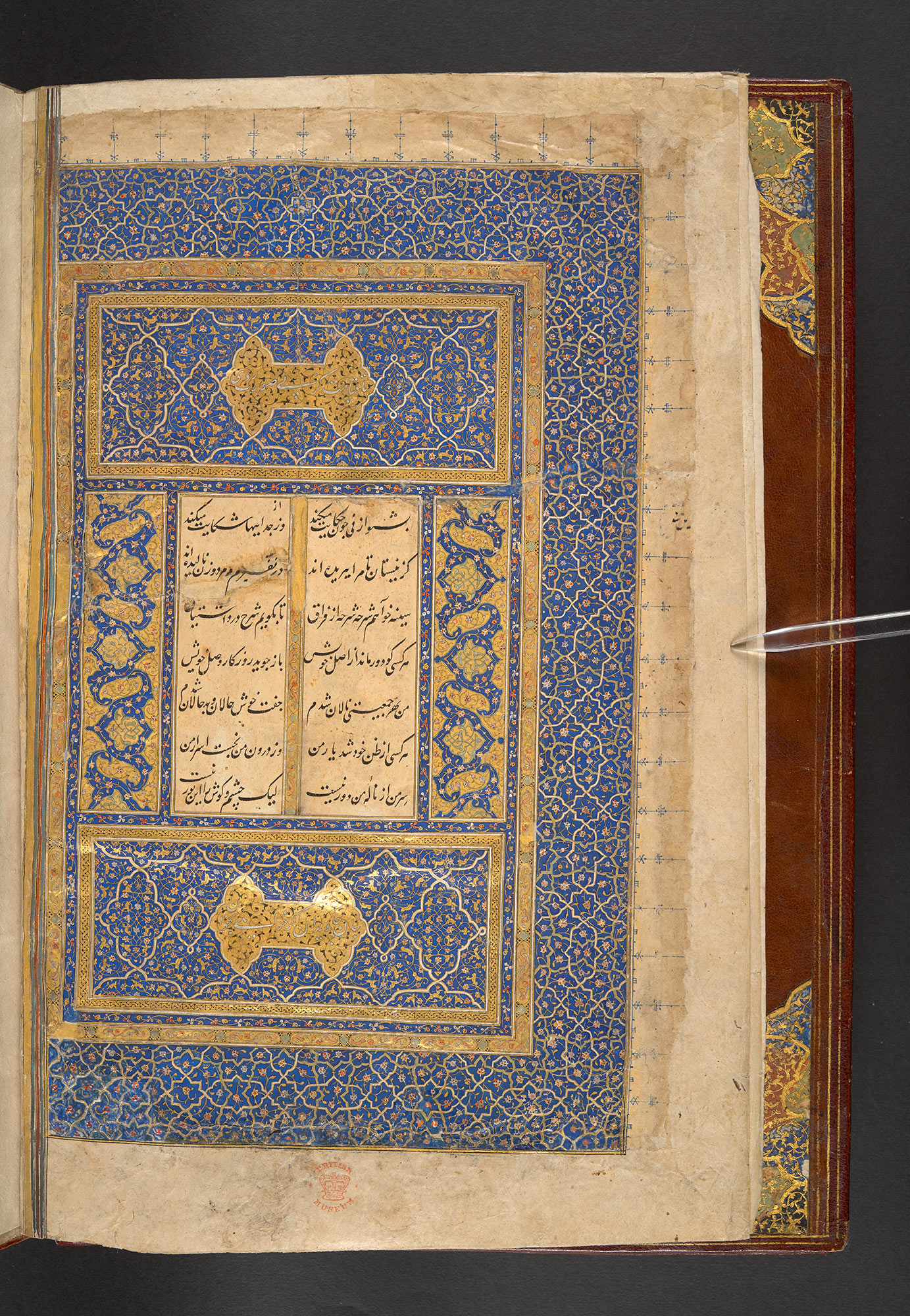

The Mas̱navī-ʼi maʻnavī by Jalāl-al-Dīn Rūmī (d. 1273) was composed in the 13th century and is a monumental work of poetry in the Sufi tradition of Islamic mysticism. Divided into six books, it has served as an inspiration for Sufis and others worldwide and is today perhaps the best known work of Persian literature (photo: British Library).

Where did Sufism begin?

Central aspects of Sufism, such as the continuous remembrance of God, love for him and his creatures and the effort to transcend the mundane concerns in favour of the eternal joys of the divine world, are clearly found in the Qur’an and the Prophet Muhammad’s exemplary character. However, Sufism as a historical phenomenon emerged in the 7th/8th centuries CE through the preaching of a movement of ascetics, and developed in Baghdad in the 9th/10th centuries around some charismatic figures, the most influential of which is the master Junayd al-Baghdadi (d. 910). From Iraq, it quickly spread throughout the rest of the Muslim territories, contributing to the conversion of the new populations that came under the control of Muslim rulers and deeply influencing the religious thought, the arts and the literatures of those areas.

Sufism changed over the centuries in its manifestations, accommodating local cultures and taking on different languages, in turn providing them with ideas and concepts that came to be part of the language, the literature and the popular culture. However, the main character of Sufism, which can be summarised with the term ‘esotericism’ (from the ancient Greek esōtérō, ‘further inside’), remained the common denominator of the multiple manifestations of Sufism in virtually every time and place. The esoteric essence of Sufism points to the double meaning of being within an individual devotee, and within the inner circle of the chosen ones. Sufi terminology uses the complementary terms of zahir (‘that which is external’, the exoteric) and batin (‘that which is inner’, the esoteric); these terms refer to the fact that everything existing has an outer appearance and an inner reality. From the natural phenomena of the cosmos, to human beings and the Qur’an itself, everything has a literal, immediately perceptible meaning and a deeper, true reality. The Sufi’s aim is the attainment of this true reality, and thus Sufism is described as a path from the exoteric to the esoteric, the ultimate station of which is the knowledge (ma‘rifah) of God and union with him. This path, the Sufis believe, can be attained through a series of rituals and practices that vary across the different mystical schools, but which cannot be effectively performed without the guidance of a master (shaykh) who has already trod the whole path, whose authority is certified through an uninterrupted chain (silsilah) of other masters (often referred to as awliya’ Allah, ‘friends of God’, because of their intimacy with the secrets of the Divine) that connects him back to the Prophet Muhammad.

An imperial copy of Jami’s Nafaḥāt al-uns, copied for the Mughal Emperor Akbar in 1604–1605. It consists of 567 biographies of Muslim saints and mystics, dating from the 8th to the 15th century, followed by a section on Sufi poets and ending with accounts of female saints. The author was the celebrated Persian poet, scholar and Sufi, ʻAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī who died at Herat in 1492 (photo: British Library).

The spiritual chain connecting the saints to Muhammad highlights the importance of the biographical genre in Islam in general, and Sufism in particular. The biographical literature on Muhammad serves as both a repository of information about the life of the Prophet and as a means for the development of a devotional attitude towards him as an exemplary model of conduct. Biographies of Sufi saints were produced by Sufi literati with the double aim of preserving information about important masters, and of providing practitioners with examples of asceticism, devotion and piety. Sufi biographies often focus on reports (akhbar) combining noteworthy events, morality tales, and miraculous stories where historical reality is mixed with hagiographical elements, rather than a comprehensive account of the saint’s life. Among these works the Persian mystical poet Farid al-Din ‘Attar’s (d. 1221) only surviving prose work, the Tadhkirat al-awliya’ (Biography of the Saints), stands out. The Tadhkirat is a collection of the biographies of seventy-two Sufi saints, beginning with the sixth Imam of Shi‘a Islam, Jaʿfar al-Sadiq (d. 765), and ending with the life of the celebrated Sufi martyr Mansur al-Hallaj (d. 922), encompassing such great mystics as Hasan al-Basri, the female saint Rabi’a al-ʿAdawiyya, and the great jurists Abu Hanifa and al-Shafiʿi.

An autograph copy of the Mughal Princess Jahanara’s Muʼnis al-arvāḥ (‘The confidant of spirits’), a biography of the famous Sufi saint Muʻin al-Din Chishti (photo: British Library).

The doctrine, the shaykh and the Sufi orders

The Sufi is expected to go through ascending spiritual stations (maqamat) ultimately conductive to a direct experience of the truth. This path may encompass visionary experiences and ecstatic states (hal). It is often described as moving up to the stage of ‘annihilation’ (fana) of the self, with the final goal being the return of self and subsistence in God (baqa). Existence in the world of multiplicity is therefore somehow illusory, true existence being an attribute of the only God, i.e. it is an attribute of unity. Among the celebrated Sufi masters who better formulated this idea (often referred to as the doctrine of the ‘unity of the being’, wahdat al-wujud), is the Andalusian metaphysician Muhyi al-Din Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240), who exerted an influence on subsequent Muslim thought comparable to that exerted by Plato on Western philosophy. Faithful to the Qur’anic tenet that nothing on earth is permanent except the face of God (Q. 28. 88: All things perish, except His Face), the Sufi’s ultimate goal is to get rid of their ego and the world of multiplicity to subsist in communion with God in the abode of unity.

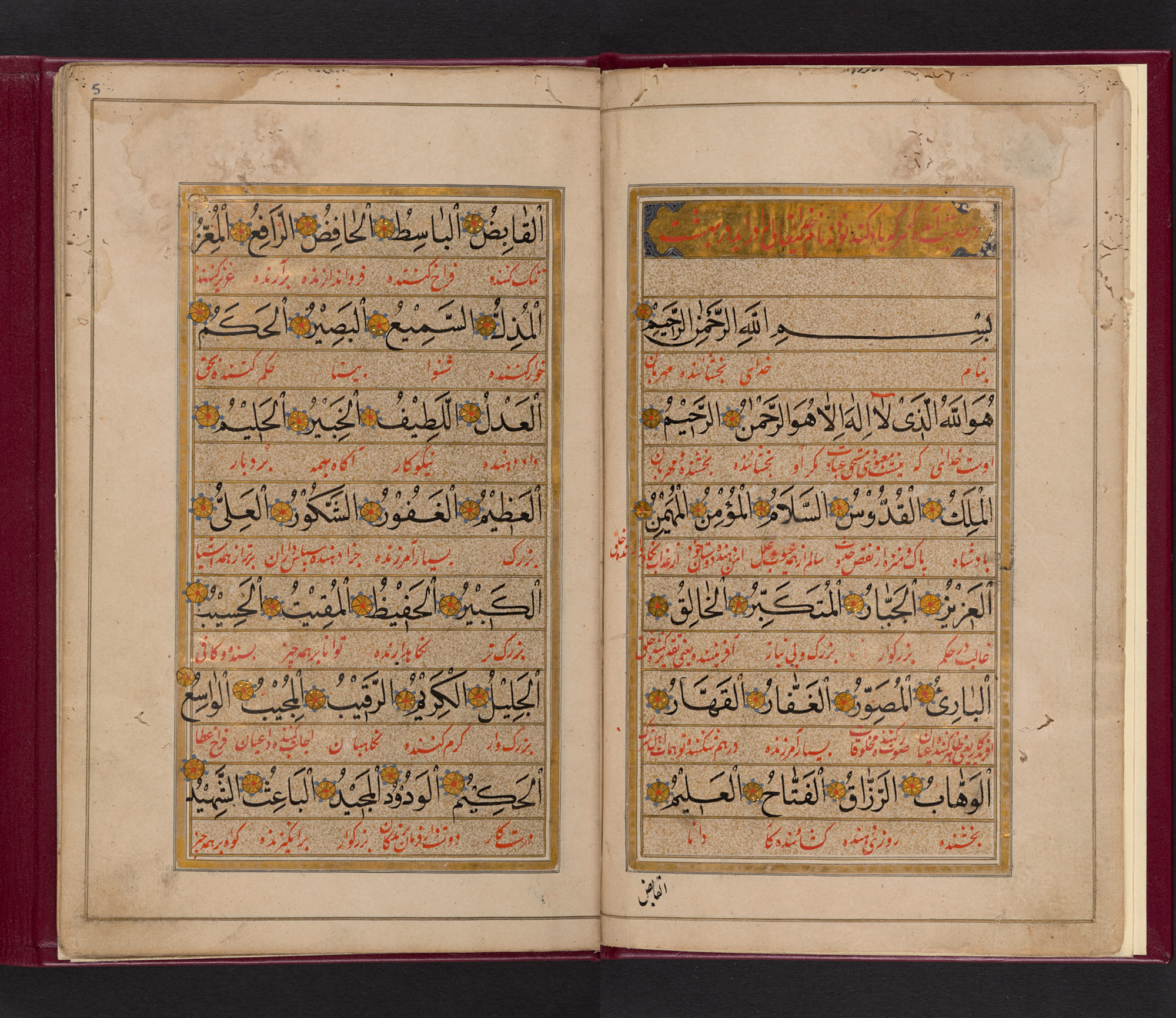

An 18th-century collection of Sufi teachings, prayers and invocations (photo: British Library).

The starting point of this journey is initiation into a Sufi order (tariqah). Sufi initiation, as well as being a ritual believed to transmit a transformative spiritual influence (barakah), represents a formal covenant (bay’a) through which the disciple commits to obey the master. The bond between the shaykh and the disciple (murid) is therefore a very important one. In the 10th and 11th centuries the model of this relationship reshaped Sufism, from a network of informal and often trans-regional mystical and ascetic circles, to a series of institutions with a defined hierarchical structure, often endowed with a high social relevance, financial resources and sometimes political clout. It is the social standing of the shaykh as the head of these institutions that facilitated the birth of what has been defined as ‘organised Sufism’ or ‘tariqah Sufism’, which is the form of Sufism still prevalent today.

How do Sufis interpret the Qur’an?

In order to delve into the batin, or the inner meaning, of the Qur’an, Sufis made major contributions to the Islamic exegetical tradition. Sufism offered a creative insight, firmly rooted, however, in the scriptural and authoritative tradition. In Sufi exegesis, the esoteric meaning of the text is explored, and the understanding of the scripture is looked at as a veritable mystical practice that opens up ways for a transformative knowledge. For Sufis, understanding the Qur’an is a religious experience rather than an intellectual and rational one.

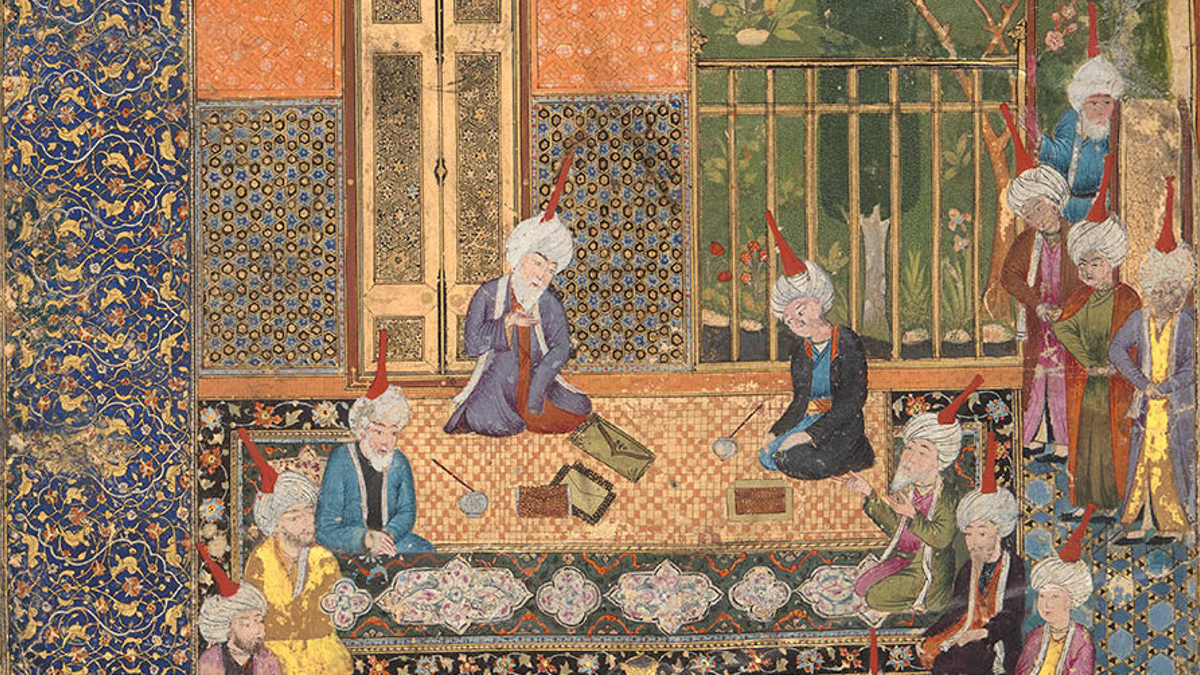

Sufi authors such as Abd al-Rahman Sulami (d. 1021), Abu al-Qasim al-Qushayri (d. 1073), Rashid al-Din Maybudi (fl. early 12th century) and Ibn 'Arabi all wrote works of Qur’anic exegesis that had a lasting impact on the subsequent exegetical tradition. Some exegetical material produced by Sufi writers is written in poetical forms. One such case is the celebrated Masnavi, a voluminous poem famously praised in the Persian-speaking world as ‘the Qur’an in the Persian language’. Written by Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273), one of the greatest stars of the firmament of Sufi poetry, the Masnavi is so closely informed by the Qur’an and its mystical interpretation that it can be regarded, as well as the poetic masterpiece that it is, as a work of Qur’anic exegesis in its own right.

An illustrated 16th-century copy of the Mas̱navī-ʼi maʻnavī by Jalāl-al-Dīn Rūmī (d. 1273) (photo: British Library).

Qur’anic pericopes and Sufi poetry: Yusuf and Zulaykha

Sufi poets often reflected on the Qur’anic text and used it as an inspiration for their poems. Among the literatures heavily informed by Sufi thought, Persian literature, in particular poetry, has a special place. It has served as education for the Persian-speaking peoples across the classes since its inception.

The pericopes in particular (narrative units often illustrating stories of pre-Islamic prophets) have been a source of Qur’anic inspiration to Persian poets. The Qur’an is punctuated by these pericopes, narrating stories of Jesus, Moses, Jonah and other biblical characters. The story of Joseph and Zulaykha, widely known as the story of Joseph and Potiphar in the Book of Genesis, was particularly fascinating to the Sufi imagination, as it narrates the story of a young and handsome man (Jospeh/Yusuf) who resists the advances of the older and wealthy Zulaykha, who is identified as the wife of the Egyptian officer who bought Yusuf as a slave from his brothers (Zulaykha is not named in Genesis, while Potiphar is not named in the Qur’an).

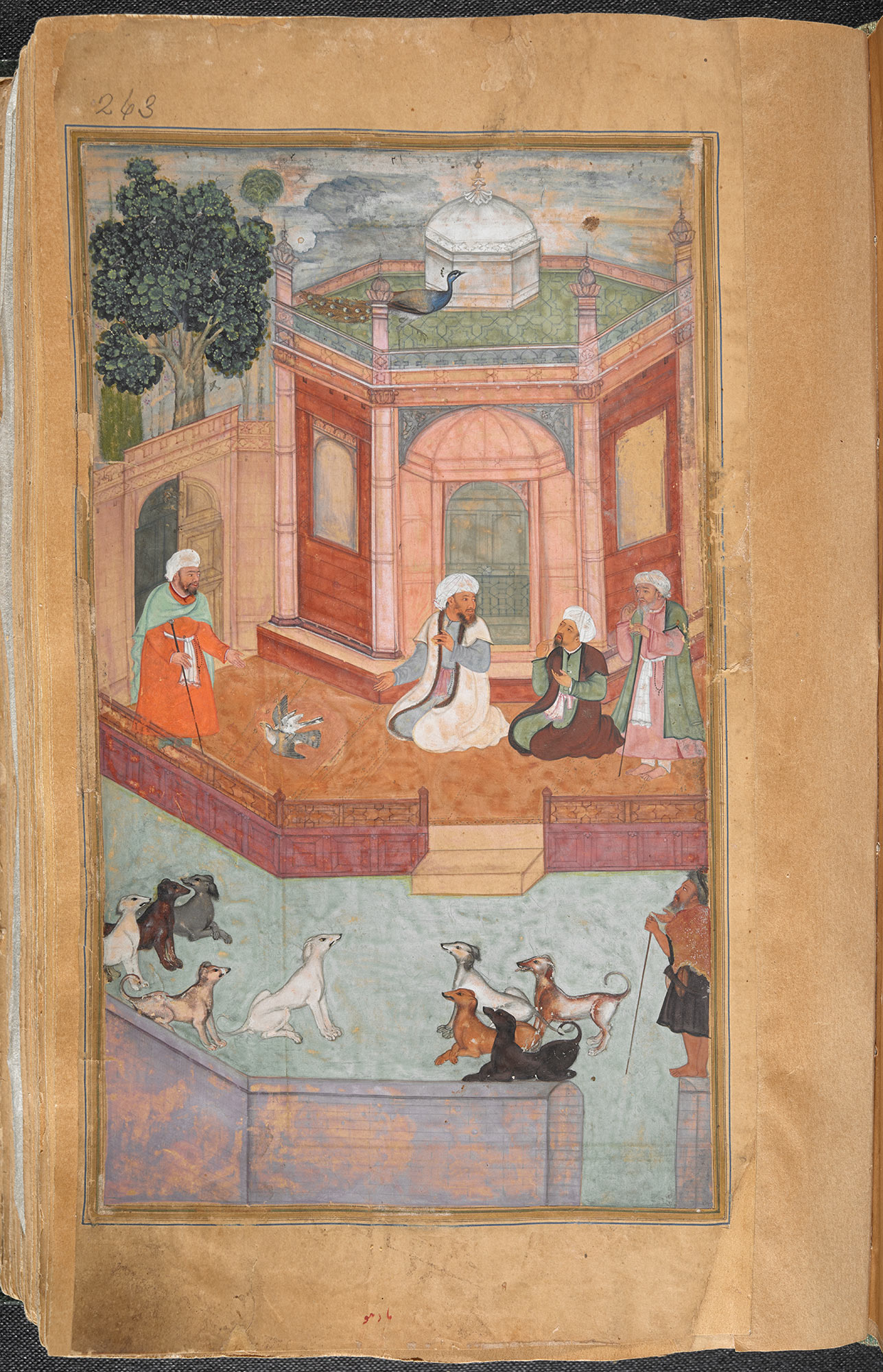

A deluxe 16th-century Safavid copy of Jami’s allegorical romance Yusuf and Zulaykha. Joseph/Yusuf and Zulaykha are depicted here in the garden (photo: British Library).

The story has been narrated in Persian poetry a number of times by different poets, and it underwent several elaborations and expansions. The most famous of these poetic renderings is the one offered by the 15th-century Persian Sufi poet Abd al-Rahman Jami, who devotes one of the seven books of his Haft-awrang (Seven Thrones) to the story. Jami’s Yusuf and Zulaykhabecame a classical example of Sufi interpretation of Qur’anic narrative material expressed in verses, and one of the masterpieces of Sufi erotico-mystical poetry. In the work, love for the Divine is addressed through the symbolisation of the human characters of the protagonists, and Jami masterfully blends different streams of the intellectual history of Islam: Avicenna’s philosophical cosmology, Ibn ‘Arabi’s metaphysics and the tradition of classical Persian mystical poetry.

Sufism poetry and the quest for truth: ʿAttar’s Mantiq al-tayr

Love is one of the preferred themes of Persian Sufi poets, both for its narrative potential and for its relevance as a spiritual driving force. The spirits of the friends of God, the Sufi theoretician of erotic mysticism Ruzbehan Baqli (d. 1210) says, became intoxicated with the Divine word and fell in love with God, the eternal beloved, through the contemplation of his beauty. This attractive power leads the Sufi to shed all traces of individuality and temporality, attaining the ultimate goal of annihilation and subsistence in God, which is the last station of the path. Sufi poets have described this union in countless ways, relying on their creative imagination and their visionary experiences, coupled with masterful poetical skills.

Among the most successful and imaginative Sufi poets is the already mentioned Farid al-Din ‘Attar. ‘Attar is the most important Persian Sufi poet of the second half of the 12th century, and is best known for his Mantiq al-tayr (The Conference of the Birds). This work is often regarded as the finest example of Sufi poetry after that of Rumi.

A late Timurid copy of Mantiq al-tayr (‘The Conference of the birds’) by Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. Depicted here is the vain peacock, who was banished from Paradise because of his pride (photo: British Library).

This epic poem vividly depicts the tale of thirty birds on a journey to find their supreme master, called the Simurgh. In the end the birds realise that they themselves are the Simurgh, the name being composed of the two Persian words si (thirty) and murgh (bird). The quest symbolises the human soul’s quest to find its true reality, which is ultimately the self freed from the delusion of multiplicity. ‘Attar’s Conference of the Birds draws on the work of another great Sufi master, Ahmad Ghazali (d. 1126), who had written a similar story half a century earlier, but ‘Attar's masterful craft elevated it to the fame it has today. ‘Attar’s epic masterpiece has also been turned into a number of musical and theatrical plays in the Persian world as well as in the West, and its colourful stories provided abundant material for illustration in Persian miniature painting.

Dr. Alessandro Cancian is Senior Research Associate at the Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, where he works on Shiʿi Sufism, Qur’anic Exegesis and the intellectual and religious history of pre-modern Iran. A historian of religions and anthropologist by formation, he has published books and articles on religious education in Shiʿi Islam, Shiʿi Sufism and Qur’anic exegesis. He edited Approaches to the Qur’an in contemporary Iran (Oxford University Press, 2019).

( Source: Republished under the Creative Commons License from the British Library ).

Topics: Dua (Supplication), History, Metaphysics, Poetry, Quran, Sufism Values: Knowledge, Love, Spirituality

Views:6876

Related Suggestions