The History of al-Masjid al-Haram and the History of the Ummah

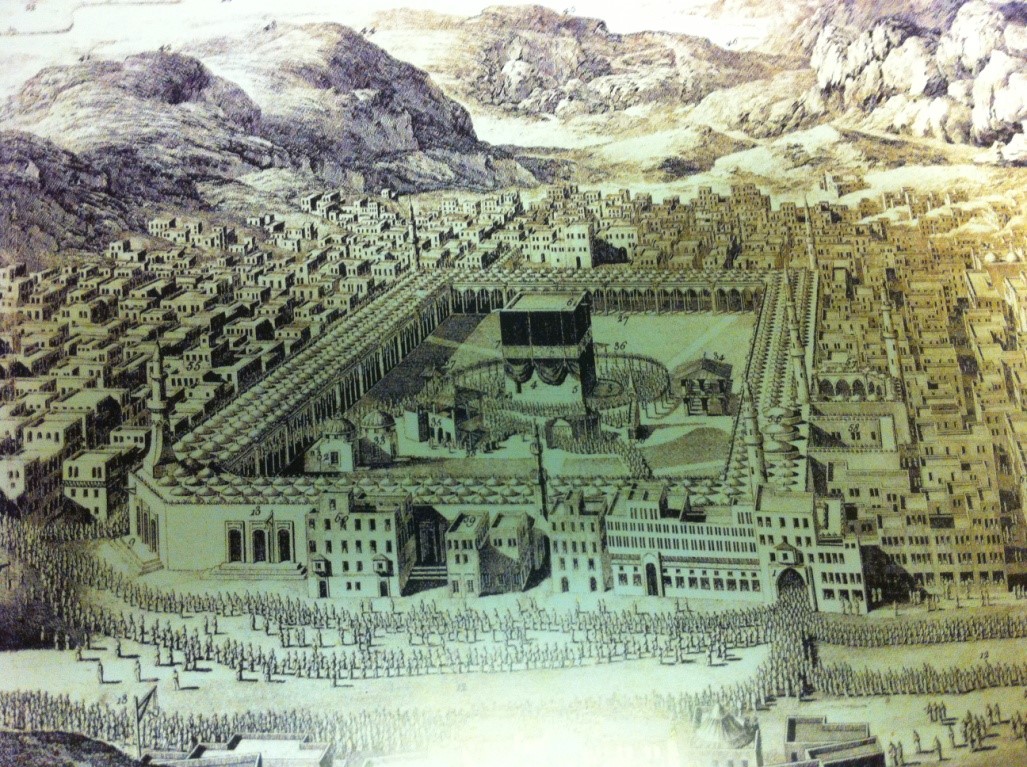

After the epoch of al-Khulafa’ al-Rashidun (rightly-guided Caliphs) and until the modern Saudi era, al-Masjid al-Haram underwent a number of reconstructions and expansions. Those who made the most remarkable impacts on the Mosque, regardless of whether they enlarged it or just renovated some sections thereof, were:

1) ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr whose expansion -- third in a sequence -- took place from 65 AH/ 684 CE;

2) Umayyad Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik b. Marwan whose restoration works happened from 75 AH/ 694 CE;

3) Umayyad Caliph al-Walid b. ‘Abd al-Malik whose expansion -- fourth in history -- occurred from 91 AH/ 709 CE;

4) Abbasid Caliph Abu Ja’far al-Mansur whose expansion, which was fifth in succession, took place from 137 AH/ 754;

5) Abbasid Caliph Muhammad al-Mahdi whose colossal and sixth in succession expansion took place in two stages: from 160 AH/ 776 CE and from 164 AH/ 780 CE, the latter stage having been completed by his son al-Hadi who in 169 AH/ 785 CE succeeded his father as fourth Abbasid Caliph;

6) Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tamid ‘Alallah whose renovation works happened from 271 AH/ 884 CE;

7) Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tadid Billah whose lesser seventh expansion occurred from 281 AH/ 894 CE;

8) Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir Billah whose minor and eighth in history expansion came to pass from 306 AH/ 918 CE;

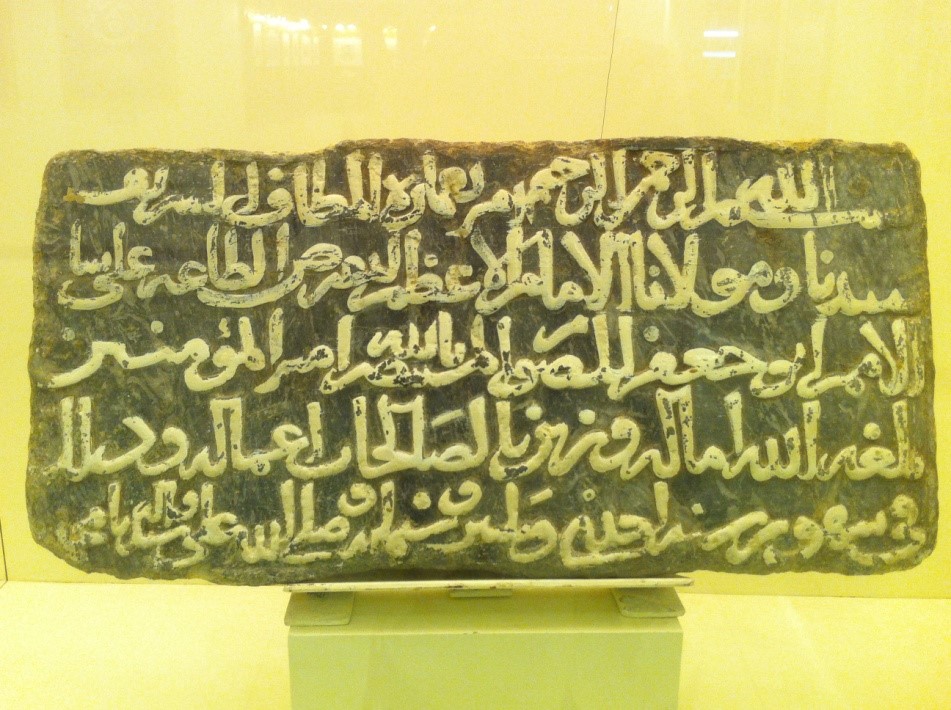

9) Restoration works by the Mamluks that occurred from 803 AH/ 1400 CE and from 882 AH/ 1477 CE;

10) The significant reconstruction efforts by the Ottoman Turks from 972 AH/ 1564 CE and from 984 AH/ 1576 CE.

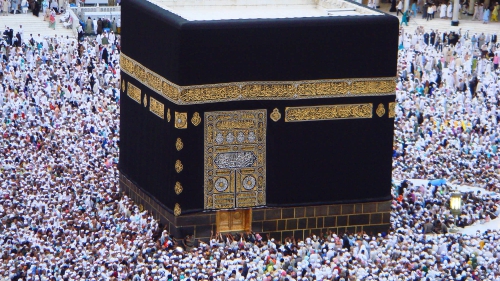

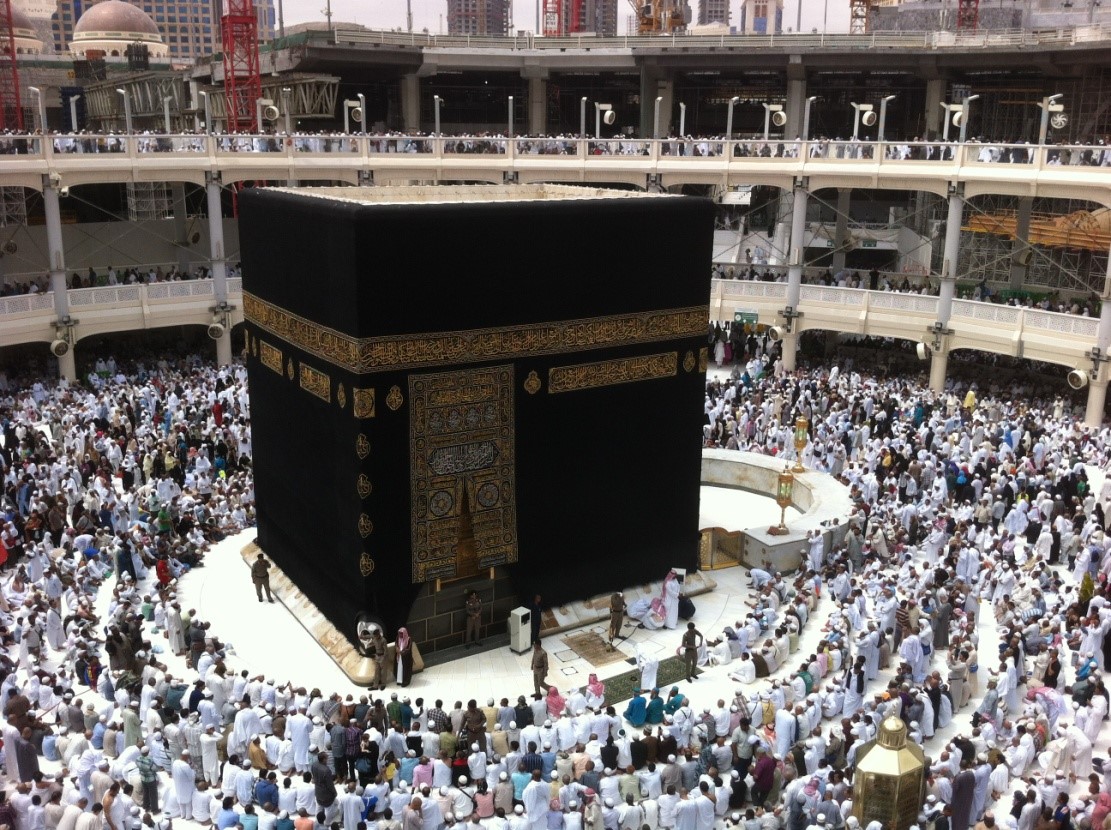

The existence of al-Masjid al-Haram, at once as a concept and sensory reality, was a microcosm of the existence of the whole of Islamic community (ummah), also as an idea as well as an actual reality. In the same vein, the dynamic intensification and development of the former echoed the equally vibrant evolution and growth of the latter. The two were entwined in a causal relationship which was so reciprocal that it was not always clear which one exactly, and to what extent, was the cause, and which the effect, and to what extent. What was clear, however, was that when one of them functioned properly and prospered – mainly due to the people’s spiritual and civilizational excellence -- the other did so, too. But if it malfunctioned and suffered – again mainly due to certain people’s waywardness and grave misdeeds -- the other correspondingly did so, too.

Thus, for example, during the second civil war, or fitnah, (61-73 AH/ 680-692 CE) the highlight of which was ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr’s refusal to take an oath of allegiance to Yazid, the son and heir presumptive of Mu’awiyah b. Abi Sufyan, the first Umayyad Caliph – as well as to the subsequent Ummayyad sovereigns – which resulted in a series of prolonged disputes, conflicts and, inevitably, bloody confrontations. Since the seat of ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr’s activism was in Makkah, the city was besieged on a couple of occasions and severely damaged.

During the first combats in 64 AH/ 683 CE, following a protracted siege of the city, the Umayyad army took control virtually of the whole of the city, except the area of al-Masjid al-Haram and its vicinity. Besides establishing his command post on its grounds, ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr together with his soldiers also fortified himself in the Mosque. They constructed from wood and tree branches some makeshift shelters as protection against the sun and the stones launched from Umayyad catapults which were employed as part of the siege of the city. Over the Ka’bah, a wooden structure covered with mattresses had likewise been erected to protect it from the bombardment.

For the duration of the siege, naturally, the functioning of al-Masjid al-Haram was seriously hindered. Owing to the bombardment by catapults, the structure of the Ka’bah was badly damaged and weakened. In addition, one of the companions of ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr lit a fire and a spark flew off and set alight the combustible sections of the Ka’bah, namely the kiswah or cloak and the wooden materials from which its roof completely and walls partially were made. Al-Hajar al-Aswad or the Black Stone was also scorched and hence, became black. It burst asunder into three fractions. However, according to another account, ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr erected a tent nearby as part of his command post. Whenever a man of his got injured, he would place him inside the tent. But a person from the people of Syria came one day with a fire on the top of his lance and burnt down the tent. The day was extremely hot and a wind wafted a spark from the burning tent onto the building of the Ka’bah, which then itself burst into flames. At any rate, reconstructing at once the Ka’bah and al-Masjid al-Haram became thus a necessity.

So, therefore, as soon as he could, ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr reconstructed the Ka’bah, restoring it to the original foundations of Prophet Ibrahim – having earlier been rendered shorter on the northwestern side by the Jahiliyyah (Ignorance) Quraysh during their own reconstruction exercise by approximately three meters, at a location where crescent shaped Hatim or Hijr was consequently built. ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr also repaired and significantly improved and enlarged al-Masjid al-Haram.

However, no sooner had ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr been killed and the Umayyad rule completely restored, than the Ka’bah was again trimmed and reinstated to its earlier Qurayshi size and form. Though it was not expanded, some remarkable improvement work was done on al-Masjid al-Haram as well. Obviously, the Umayyad establishment was determined to annul and obliterate as much of ‘Abdullah b. al-Zubayr’s legacy as possible, in particular with regard to the first, most valuable and so, most venerated Mosque on earth.

All those events unmistakably exhibited how susceptible to political manipulation the Ka’bah and al-Masjid al-Haram have been due to their civilizational significance, position and role, with different personalities and parties trying to gain political mileage thereby. It is no surprise that the trend materialized and started gaining momentum as soon as the earliest political disagreements on the Muslim scene fully evolved into political and, to some extent, even ideological disintegration of the community, leading in turn to gory military confrontations that quickly assumed epidemic proportions. There were those who were fully cognizant of the matter, though, and could foresee the drawback. For example, as part of Abdullah b. al-Zubayr’s consultations with the people as to what to do to the scorched and ruined Ka’bah, a companion Abdullah b. ‘Abbas proposed: “Leave it in a state of which the Prophet (pbuh) approved (that is, do not destroy, nor enlarge it). I am afraid someone will come after you who will destroy it again. Then, others will come thereafter who will also destroy and rebuild it, until people (as a result of a trend) become indifferent and even disrespectful towards its (the Ka’bah’s) sanctity. Why don’t you just mend it…?”

Another symptom of the said sensitive susceptibility of the Ka’bah and al-Masjid al-Haram to potential exploitation was an incident between the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid – or his father Caliph al-Mahdi, or grandfather Caliph al-Mansur, as per another account – and Malik b. Anas, a leading scholar of the second Hijrah century and the founder of one of the four Sunni schools of jurisprudence. Caliph Harun al-Rashid expressed his desire to annul the alterations of the Umayyads to Abdullah b. al-Zubayr’s work to the Ka’bah, restoring the latter’s original dimensions and plan, but Malik b. Anas disagreed and strongly advised the Caliph to change his mind because constant demolition and rebuilding is not respectful and would become a toy in the hands of kings. Each one would want to demolish and rebuild the Ka’bah and people, consequently, would lose due reverence for it. Al-Fasi commented on this narrative that Malik b. Anas resorted to the principle of repelling harm (dar’ al-mafasid) at the expense of inviting benefits (jalb al-masalih) which is a well-known and established Islamic principle.

Furthermore, when the ideological confrontations between the Sunni Abbasids in Iraq and Shi’i Isma’ili Fatimids in Egypt were at an all-time high in the 11th and early 12th centuries (5th and 6th centuries AH), each party laying claims to the mantle of Islamic caliphate, Makkah with its al-Masjid al-Haram was again greatly victimized and manipulated, for one of the conditions stipulated for legitimate caliphate and legitimate caliphs was that the two harams (sanctuaries) in Makkah and Madinah be under their control and authority and that caliphs’ names be mentioned during Friday Jumu’ah prayers from the minbar (pulpit) of al-Masjid al-Haram. This in turn triggered an intense rivalry between the two poles in maintaining and whenever necessary mending al-Masjid al-Haram, to the point where sincerity towards and love for the latter was not always the case, and where the purpose and interests of al-Masjid al-Haram were attempted to be influenced and subjugated to some political and partisan interests and objectives. For example, while chiefly the subsequent Abbasid caliphs clothed or draped the Ka’bah with black cloth (kiswah), because black was their dynastic color – a tradition which was not necessarily always the case with the earlier Abbasid sovereigns -- the Fatimids, on the other hand, when Makkah was under their control, did the same with white cloth or kiswah, also because white, in a visual contrast to their sworn Abbasid foe, was their official color. Following the custom of the Abbasids, the Ka’bah is still covered with black brocade cloth on which embroidered in gold are various verses from the Holy Qur’an as well as other calligraphic captions.

If truth be told, similar fates used to befall al-Masjid al-Haram whenever, and especially within the confines of the Arabian peninsular, serious ideological and military threats were mounted against the Abbasid leadership and their administration which were concentrated in Iraq. An example was the case of the Qaramitah or Qarmatians who were a syncretic religious group that combined elements of Isma’ili Shi’ism with Persian mysticism. The Qarmatians flourished in Iraq, Yemen and especially Bahrain during the 9th to 11th centuries (3rd and 5th centuries AH), taking their name from Hamdan Qarmat, who led the sect in southern Iraq in the second half of the 9th century (3rd century AH). They were most famed for their unorthodox views and practices, as well as for continuous revolts against the ‘Abbasid Caliphate and as such, orthodox Islam. The Muslim world was outraged when during the Hajj season of 318 AH/ 930 CE Makkah was sacked, al-Hajar al-Aswad or the Black Stone of the Ka’bah stolen and the Zamzam Well desecrated with corpses.

Without a doubt, it was during those and similar occasions that the city of Makkah and its al-Masjid al-Haram suffered most. It was not rare that violent physical clashes between different political and religious groups then transpired and innocent blood spilled, looting and robberies were endemic whereby the pilgrims from outside were most affected, and various acts of harassment and oppression were customary. Such were times when fear and angst replaced safety and security, and gloom and sadness eclipsed exuberance, joy and happiness that are typically associated with the sanctuary of Makkah. There were even years when the Hajj (pilgrimage) had to be cancelled altogether. At other more recurring times, the pilgrims from a certain region, or even regions, could not make it to the holy lands on account of specific socio-political, economic and security factors, certain pilgrimage rites were partially or completely affected, and the overall pilgrimage services and facilities rendered to the pilgrims were ineffective and lacking.

It goes without saying that it was because of all this that in 442 AH/ 1050 CE, the city of Makkah was a very small, poor and abandoned by many, city. This was a description provided by Naser Khosraw, a famed 5th AH / 11th AC century traveler from Iran who visited Makkah when the power of the Shi’i Isma’ili Fatimids in Egypt was at its zenith and when they were engaged in some of the deadliest conflicts with the Sunni Abbasids and their Saljuki custodians. By profession, Naser Khosraw was a Shi’i Isma’ili philosopher, poet, writer and scholar. He wrote in his Book of Travels that “I reckoned that there were not more than two thousand citizens of Makkah, the rest, about five hundred, being foreigners and mojawers (temporary residents). Just at this time there was a famine, with sixteen mounds of wheat costing one dinar, for which reason a number of people had left. Inside the city of Makkah are hospices for the natives of every region – Khorasan, Transoxiana, the Iraq, and so on. Most of them, however, had fallen into ruination. The Baghdad caliphs had built many beautiful structures, but when we arrived some had fallen to ruin and others had been expropriated.”

Suggesting the precarious security condition of the city, Naser Khosraw further remarked that Makkah is situated low in the midst of mountains “such that from whatever direction you approach, the city cannot be seen until you are there.” “Wherever there is an opening in the mountain a rampart wall has been made with a gate.”

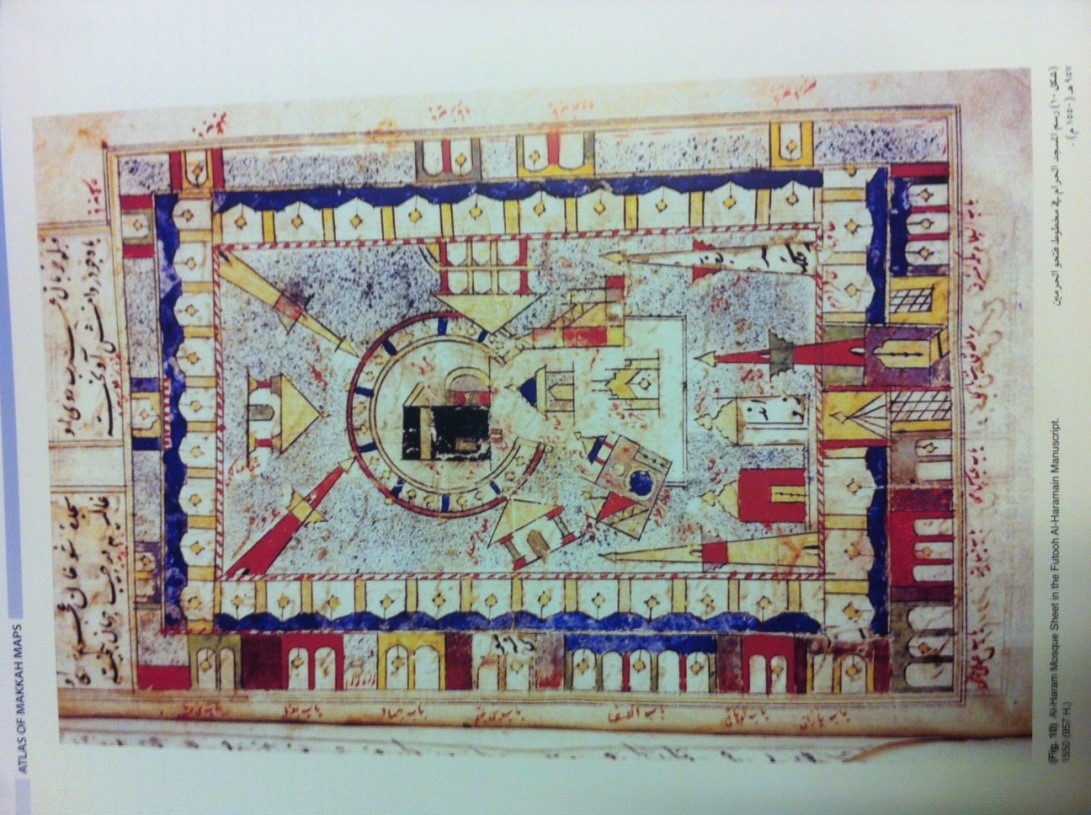

Unfortunately, neither architectural morphology nor the functional performance of al-Masjid al-Haram was spared the predicaments that were upsetting and holding back the core of the Muslim world spiritually and intellectually. Hence, as a further illustration, just around the epoch in question, daily prayers inside al-Masjid al-Haram were conducted at different times according to the four most widely accepted Sunni Schools of jurisprudence (madhhab), and at four different locations of the Mosque. Because they were most numerous in Makkah, the followers of the Shafi’i School of law would pray first, and would do so behind maqam Ibrahim (Ibrahim’s station). Their prayers would be followed by the prayers of the followers of the Maliki and Hanbali Schools of law. They were conducted behind the Yamani corner and at a place between the Yamani corner and the corner with the Black Stone respectively, and were performed concomitantly. Lastly, the followers of the Hanafi School would pray facing the Ka’bah’s northwestern side where Hijr Isma’il, or Hatim, as well as the spout or downpipe (mizab) are. This was the situation with all daily prayers except the Maghrib or after-sunset Prayer. Since the time between the Maghrib and the subsequent ‘Isha’ or night-time Prayer is short, the former would be performed simultaneously by all four Schools. This, however, was often a cause of widespread confusion and chaos as voices of prayer leaders and mu’adhdhins (prayer announcers) were overlapping and fusing.

Admittedly, this was one of the most perplexing innovations associated with al-Masjid al-Haram. It remains something of a mystery how the people could resort to such a repulsive tradition right inside al-Masjid al-Haram when harmony, unity, brotherhood, tolerance, mutual compassion and respect occupy the highest positions in the hierarchy of Islamic foremost values and virtues. According to Basalamah, the tradition originated most probably between the 4th and 5th AH/ 10th and 11th CE centuries and lasted well into the 14th AH/ 20th CE century. No wonder, then, that the air inside al-Masjid al-Haram and in the entire holy city of Makkah, especially during the annual Hajj or pilgrimage season when multitudes of people from all corners of the Muslim world would converge, was often during those trying times filled with anxiety, trepidation, mistrust and insecurity.

Ibn Jubayr, the Spanish traveler, reported that when he was in Makkah in the month of Ramadan in 579 AH/ 1184 CE, there were five simultaneous Tarawih congregations inside al-Masjid al-Haram: the Shafi’i, which had precedence over the others, Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki and even the Zaydi congregation. The last was a Shi’ah branch and followed the Zaydi Islamic jurisprudence. Ibn Jubayr refers to the parts of the Mosque that belonged to those congregations, the mihrabs (praying niches) and candles used for lighting and adornment at those specific locations.

To Ibn Jubayr, apparently, such a phenomenon was mere superficial evidence of a much larger problem that was besetting not only the holy lands, but also a majority of Muslims. He thus lamented that the quandary was more profound than it seemed and was of a convoluted intellectual and spiritual character. He observed that “the greater number of the people of these Hijaz and other lands are sectaries and schismatics who have no religion, and who have separated in various doctrines. They treat the pilgrims in a manner in which they do not treat the Christians and Jews under tribute, seizing most of the provisions they have collected, robbing them and finding cause to divest them of all they have.” Also: “The traveler by this way faces danger and oppression. Far otherwise has God decreed the sharing in that place of his indulgence. How can it be that the House of God should now be in the hands of people who use it as an unlawful source of livelihood, making it a means of illicitly claiming and seizing property, and detaining the pilgrims on its account, thus bringing them to humbleness and abject poverty. May God soon correct and purify this place be relieving the Muslims of these destructive schismatics with the swords of the Almohades (a puritanical Muslim dynasty ruling in Spain and northern Africa during the 6th AH/ 12th CE and 7th AH/ 13th centuries).” About the Emir of Makkah, Ibn Jubayr also wrote: “Such was his speech, as if God’s Haram were an heirloom in his hand and lawfully his to let to the pilgrims.” Consequently, Ibn Jubayr inferred that “there is no Islam save in the Maghrib (Muslim West where the Almohades ruled) lands.”

The bizarre tradition of having four separate congregations had more than a few implications for the interior appearance of al-Masjid al-Haram and the provision of needed facilities. Thus, there were inside the Mosque four marked maqamat or locations for each of the four Schools of Islamic jurisprudence (madhhab) and its adherents to perform five daily prayers. The spots or locations of the imams or prayer leaders were marked either by pavilions which had four columns of stone supporting a dome, and a mihrab (praying niche) built between two columns that faced the congregation, or just by a mihrab flanked by two columns of stone, or posts. Due to their long and colorful history, these simple architectural elements were sometimes even simpler, such as having only two columns of stone, or posts, without a mihrab, and at other times somewhat more elaborate and tasteful, such as having domes and arches that spanned pairs of columns with protruding hooks for hanging lamps.

The Mamluks are reported to have been responsible for actively building and upgrading some of those architectural elements during their rule and their relatively active Mosque upkeep and restoration activities. The same holds true insofar as the Ottoman Turks’ extensive rule and their architectural activities in al-Masjid al-Haram were concerned. As the ardent followers of the Hanafi madhhab, they rebuilt the Hanafi maqam, making it thereafter the largest and most elegantly built of the four maqamat inside the Mosque.

In addition, as part of al-Masjid al-Haram complex, a dozen madrasahs or colleges were also built especially by the Mamluks and Ottoman Turks wherein Islamic jurisprudence was taught in accordance with the teachings of the four Orthodox or Sunni Schools of law and for which senior lecturers from all madhhabs were engaged. By and large, initiatives such as these were hailed as significantly resourceful and productive. However, one wonders how much that was the case in the prevailing religious, social and intellectual climate, and whether the procured benefits outweighed the damages that the trend was generating and perpetuating insofar as the future prospects of the Muslim civilizational reality were concerned. This apprehension comes to the fore in particular when one bears in mind that scores of highly regarded scholars of the day never approved the religious innovations that pertained to divisions, schism, and sectarian bigotry and fanaticism, including the one relating to multiple prayers inside al-Masjid al-Haram, as well as when one bears in mind that the rulers of the day were the followers of one of those Schools of law indirectly favoring and supporting it over the others. This way, the rulers were making themselves more and more isolated from large sections of society. Also, the existing rift between the political and intellectual leadership in the principal religious and intellectual hubs of the Muslim world, that is, Makkah, was widening and steadily becoming an inveterate phenomenon.

Finally, since Sufism and funerary architecture flourished especially under the patronage of both the Mamluks and Ottoman Turks, several Ribats or Sufi hospices for the Sufis in particular, and for the poor in general, were erected in the immediate vicinity of the Mosque. When the Mamluks embarked on a significant al-Masjid al-Haram restoration project in 803 AH/ 1400 CE, it was due to a fire that had originally started in a Ribat located adjacent to al-Masjid al-Haram after a rat had pulled at the wick of a lamp. From the side of the Ribat facing the Mosque, the fire quickly spread to the latter’s wooden and as such highly combustible roof, engulfing and burning it uncontrollably. So swift and wild was the inferno that the people were unable to contain it. Wooden boards or panels, beams and marble columns were consumed or destroyed one by one, threatening thus to devastate the whole or most of the Mosque.

As regards the phenomenon of funerary architecture, or architecturally glorifying the dead, there was nothing feasible that could be done either inside al-Masjid al-Haram or in its immediate environs, in spite of some people’s strong penchant for the matter. However, opportunities abounded elsewhere, especially in the Mu’alla cemetery in Makkah as well as al-Baqi’ cemetery in Madinah, where a considerable number of rather moderate tombs and mausoleums were constructed. Lots of superstitions and religious innovations, normally associated both with unorthodox Sufism and funerary architecture, were reported to be widespread.

Topics: Kabah, Makkah (Mecca), Masjid Al Haram

Views:22949

Related Suggestions