The Muslim Agricultural Revolution

Printed From: IslamiCity.org

Category: General

Forum Name: Science & Technology

Forum Description: It is devoted for Science & Technology

URL: https://www.islamicity.org/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=2738

Printed Date: 11 December 2024 at 6:37pm

Software Version: Web Wiz Forums 12.03 - http://www.webwizforums.com

Topic: The Muslim Agricultural Revolution

Posted By: rami

Subject: The Muslim Agricultural Revolution

Date Posted: 24 October 2005 at 6:04am

|

Bi ismillahir rahmanir raheem

http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/AgricultureRevolution2.pdf - Medico-botanical books have been produced since the dawn of civilization; records from Egypt, Mesopotamia, China and India reflect a tradition that existed before man discovered writing. Conversely, nothing in the West evidences such antiquity. The first herbal in the Greek language was written in the 3rd century B.C.E. by Diocles of Carystus, followed by Crateuas in the 1st century C.E. The only consistent work that has survived is by Pedanios Dioscorides of Anazarba "De Materia Medica" (65 C.E.). He remains the only known authority amongst the Greek and Roman herbalists. The first treatise written on agriculture in the West was just after the fall of Carthage; it was a Roman Encyclopaedic work written by Cato the Elder (234-149 B.C.E.) on medicine and on farming that was called "De Agricultura", the oldest complete Latin prose on this subject. However, the stability of the world in which these works were compiled came to an end with the disintegration of the Roman Empire. In places where the authority of the empire no longer existed, its haphazard replacement by the early stages of feudalism brought little stability. Conflicts for the possession of the land were liable to break out anywhere. Civilization was near to collapse and all development halted. This dismal situation prevailed until the advent of Islam (7th century C.E.). In 711 C.E., within a century of the establishment of Islam, the area under Muslim influence had become one of robust economic development capable of yielding the wealth necessary to finance the protection of an area stretching from the foot of the Pyrenees to the frontiers of China. The widespread patronage of intellectual works was a key factor in this development and this resulted in the flowering of Islamic culture and civilization in the Muslim world.

This civilization had such momentum that - despite constant threats of invasion and internal dissension - huge strides were made in agriculture, medicine and science. Hence a wide range of raw materials and the means of adapting them for curing illnesses and for enhanced forms of nutrition became available.

This great movement in agriculture was largely due to central government sponsoring an extensive network of irrigation canals. In the Near East good results were achieved. However, in the West the situation was less promising. The Iberian peninsula subsistence level agro-economy was only rudimentary. In fact it was defined by race. The Visigoth herder overlords jealously protected their stock-rearing interests whilst their conquered subjects produced wheat, barley, grapes, olive oil and a few vegetables, all inherited from their previous Roman masters. Thus the only links between the two systems were those of tribute or taxes. Once the Muslims had assumed control of the province, there was a need to define which crops to cultivate. Fortunately, the Arab botanical range was already extensive and growing rapidly. In their territorial expansion, the Muslims had come across plants and trees, which were hitherto unknown to them, whilst their merchants brought back exotic plants, seeds and spices from their many voyages. Many of the more valuable crops such as sugar cane, bananas and cotton needed plenty of water or at least a monsoon season. Thus to cultivate them, a widespread artificial irrigation system would be needed. Artificial irrigation was in fact better known to the Muslims than the crop rotation system of colder European lands where it was felt necessary to leave the land fallow, i.e. to recover, for one year in three or four. However, artificial irrigation implied a need to raise water by several metres to guarantee a constant flow within the system. An ideal device existed for such tasks in the form of the Noria, Na?ura, the various forms of which represent a subject that merits its own particular study. Hence the Noria became the basis of sophisticated irrigation systems. The use of Norias spread rapidly to the extent that, in some areas, the water system became state property to ensure equitable distribution. In the Valencia area alone some 8,000 norias were built for the needs of rice plantations. Correct calculation of levels was essential, a task that the successors of Roman agrimensores with their chains of specific length were ill-equipped to perform. In this, the Muslims had the advantage of the advances they had made in mathematics thus making triangulation possible and hence the accurate measurement of height. The Muslims did not waste time in haphazard agricultural trials, but achieved maximum output by learning how to identify suitable soils and by mastering grafting techniques for plants and trees. The written works and oral traditions of ancient peoples were painstakingly recorded, whilst exchanges between experts became increasingly frequent, so that in all major towns the libraries were full of learned works on agriculture. Arising as they did from a civilization of travellers, the Muslims combed the known world for knowledge and information, journeying in the harshest of environments - as far afield as the Steppes of Asia and the Pyrenees. In this context the discovery of paper stimulated on the spot detailed recording of their journeys and observations.

This plethora of records and information built up to a level that prompted the compilation of encyclopaedic works. � Kitab nabat (a treatise on plants) by Abu Hanifa Al-Dinawari (d.282/895 CE) � Al filaha nabatiya (Nabatean agriculture) by Ibn Wahshiyya (IXth century) � Al Biruni (973-1048) Kitab al saydana (Pharmacopoeia) - large pharmaceutical encylopedia � Ali B. Sahl Rabban al Tabari (d. 240/855) Firdaws al hikma � Ibn Baqunesh (Abu Othman Sa�d Ben Muhamed) (d.1052 CE) � Ibn Bassal (Abu Abdullah Muhamed Ibn Ibrahim) (d.1100 CE) By the 12th century in Al Andalus, botany was converted from its role as a purely descriptive science and achieved the status of an academic science. This century was seen as the golden age of Islamic botany with such great scholars as: � Abu'l Abbas an Nabati (Ibn Rumiyya) d. 636 AH/1239 CE � Ibn Baytar (1197-1248 CE), Tafsir kitab Diasquridus - Jami' al mufradat al adwiya wal aghdiya � Al Ghafiqi (d.1166 CE), author of "Kitab jami' al mufradat " (materia medica) . � Ibn Al ?Awwam, 12th century author of "Kitab al filaha" (treatise on agriculture) � Ibn Bajja (d. 1138 C.E.), Kitab al nabat Liber de plantis (Latin transl.), defining sex of plants. � Najib Eddin as Samarqandi (d.1222 C.E.) wrote a treatise on medical formulary. The scholars themselves conducted their experiments and taught everywhere, including mosques and weekly markets. This is confirmed by the fact that Ibn Baytar's work was recorded in Arabic, Berber, Greek and Latin whilst Al Biruni's Pharmacopoeia gives synonyms for drugs in Syriac, Persian, Greek, Baluchi, Afghan, Kurdish and Indian dialects etc� Their linguistic capabilities demonstrated their intention of spreading knowledge amongst all nations, as was the case with the distribution of the agricultural Calendar of Cordoba in the 10th century. The Calendar of Cordoba is an example of the type of information provided as an aid to agriculture.In the aftermath of the Roman Empire conquerors, such as the Visigoths, installed regimes in which the monarch, the nobility and the church fathers owned the bulk of the land, the burghers, who were in charge of municipal affairs, had less than 25 acres each, whilst the serfs were the cultivators and were yoked to the land and were sold with it. The attitude of Muslims was different since they understood that real incentives were needed if productivity were to reach levels that might significantly increase wealth and thereby enhance tax revenues. The Muslims brought revolutionary social transformation through changed ownership of land. Any individual had the right to buy, sell, mortgage, inherit the land and farm it or have it farmed according to his preferences. Furthermore every important transaction concerning agriculture, industry, commerce and employment of a servant involved the signing of a contract of which a copy was kept by each side. The second incentive principle that was gradually adopted was that those, who physically worked the land, should receive a reasonable proportion of the fruits of their labour. Detailed records of contracts between landlords and cultivators have survived with the landlord retaining anything up to one half. Thus with all the enhancements and incentives already mentioned, the stage was now set for agricultural development on a scale hitherto unknown. The motivations that prompted phases of agricultural development were of two kinds: � Political, namely conscious decisions by the central authority to develop under-exploited lands. � Market-driven, invariably involving the introduction, by means of free seeds, advice and education and by the introduction of high value crops or animals to areas where they were previously unknown. By contrast, the African countries, instead of relying on the products of their flocks for food, were now able to eat a more balanced diet that included a variety of fruits and vegetables whilst the introduction of cotton and indigo gave them a useful cash crop. Improvements in irrigation made it possible to cultivate this high value plant in the sub-Saharan countries where other dye-making plants were also introduced. In a world that had previously known only flax and wool as textiles, silk and cotton production spread rapidly. Cotton, originally from India, became a major crop in Europe (Sicily and al Andalus) and the overall result was a democratisation of what had been rare luxury goods in the past. Within a relatively short period, mankind could use a wider range of textiles for his clothing which were available in a greater variety of colours. Sugar cane, of Indian origin, was known in the 6th century at the Sassanid court. Because of the endeavours of botanists and agronomists, it spread to Egypt, Syria, Morocco, al Andalus and Sicily. Thus, within barely a century of the Muslim conquest, the landscape in the area under Muslim control had changed so radically that it is fair to describe the process of transformation as the Muslim Agricultural Revolution. The elements of the success of this revolution can be summarised as: a. The extension of the exploitable land area by irrigation. c. Incentives based upon the two principles of the recognition of private ownership and the rewarding of cultivators with a harvest share commensurate with their efforts. d. Advanced scientific techniques allowing people like Ibn Baytar to challenge the elements by growing plants, thousands of miles from their origins that could never have been imagined to grow in a semi-arid or arid climate. The introduction and acclimatization of new crops and breeds and strains of livestock into areas where they were previously unknown. Another feature of the growth of the Muslim domain was the increase in urbanization that was facilitated by scientific improvements in the fields of hygiene and sanitation. The farmer for his part benefited from the advances made in astronomy. The measurement of time and of the onset of the seasons and even the prediction of weather became more precise and reliable, as the farmer became informed of the solar movement through each zodiacal sign. He also profited from the compilation of calendars that told him when to plant each type of crop, when to graft trees, when and with what to fertilize his crops and when to harvest the fruits of his labours. Whereas in the past he had lived in a world where he rose and lay down with the sun and relied upon changes in weather to tell him when the seasons might be due, he now lived in a world where his decisions were much easier to make. It now became feasible to think in terms of growing each of his crops for a specific market at a specific time of the year. Furthermore, the same calendar that aided the farmer in his activities also carried recommendations about what to eat and what to avoid at each time of the year. This in turn facilitated the farmer's task of deciding what to plant in relation to future demand. by: Dr Zohor Idrisi, Wed 01 June, 2005 ------------- Rasul Allah (sallah llahu alaihi wa sallam) said: "Whoever knows himself, knows his Lord" and whoever knows his Lord has been given His gnosis and nearness. |

Replies:

Posted By: Community

Date Posted: 24 October 2005 at 9:12pm

|

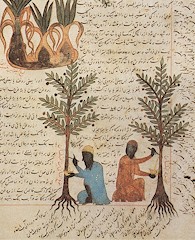

That picture to me looks like muslimeen planting trees....fruit trees, looks like olives in this case.....now where is the agricultural revolution in the arab and african world of planting trees? do they feel safe that the ends is not yet? or do they think the end is near? The prophet is reported to have said that even if tomorrow is the end and you are planting a tree then still go ahead and do it. This is a sign to the future for his ummah to plant trees. Let us do what the prophet spoke of, because it is good. Let people start planting trees en take care of them...make the lands green, is the land not given to them to do something good with it? how is it that they wish to be called the best community that was made to appear for mankind while they do not even think about making their lands green? and instead choose to be hostile to other people who are different or speak of how wrong and evil they are? Does not Allah forbid such talk about others because it maybe that they are better then their ownselves? |