|

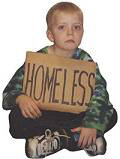

Government says Hungry Americans No Longer 'Hungry'

It hasn't the zesty political punch of that Reagan-era effort to turn ketchup into a vegetable. But really, could there be a more unfortunate time for the Agriculture Department to banish the word "hunger'' from its description of people who are, well, hungry?

Just a week before most of America sits down for that excessive meal we call the Thanksgiving feast (second- and third-day snacking while watching football is optional), came a new definition for the millions among us who are more likely to turn up at a food pantry than at a well-set dining table. They are now to be known as people with "very low food security.'' They were previously known as "food insecure, with hunger.'' Those who had some, but not much, more to eat were known as "food insecure, without hunger.'' Now they're just suffering from "low food security.''

The linguistic legerdemain doesn't change the method the USDA uses to count Americans - it says there are about 35.1 million - who are uncertain of having enough food or simply don't have enough money to buy it. The number of people without sufficient resources to get food has been climbing for five years, but leveled off in the latest survey, the department says.

But the worst-off households fared worse, with the number of people described as having "very low food security'' climbing from 10.7 million to 10.8 million. These are households in which "the food intake of some household members was reduced and their normal eating patterns were disrupted,'' because they couldn't buy food.

In a word, they went hungry.

The switch of bureaucratic jargon came about after the White House budget office questioned why the agriculture researchers actually called hungry people "hungry.'' The USDA bucked the question to the National Academies of Science, where it was determined that using the word "hunger'' wasn't entirely accurate, since the agriculture researchers can count people who say they don't have enough food - but can't necessarily describe the symptoms they experience while doing without.

Statistics just can't capture what it feels like to have a hollow pit in the stomach, to lose weight or get sick because of malnutrition.

The new wording doesn't seem malicious. But it does raise a meaningful question: Why are more than 35 million Americans going without food, or without enough of it?

About half of people who turned to a charitable food pantry last year already were living in households that received federal food stamps, the USDA's annual survey says. An even greater proportion - 66 percent of those who turned to pantries - received at least some form of federal food assistance, including school lunches and the feeding program for women, infants and children.

"It's a 10-year story,'' says Jim Weill, president of the Food Research and Action Center. The 1996 welfare overhaul threw millions of legal immigrants and able-bodied adults without children out of the food stamp program. Though Congress restored eligibility little by little, it neglected to alter the program in ways that would stretch food-assistance dollars far enough to keep up with the economic changes buffeting low-income people.

Food stamp allotments assume that a family spends at least some of its own money on food. But depressed and stagnant wages for unskilled workers, coupled with astronomical rents, now leave them without the cash the government assumes they'll have to feed themselves. The average food stamp benefit allows $1 per person, per meal, according to Dottie Rosenbaum, a food assistance expert at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. "They don't have ... other income to purchase food,'' Rosenbaum says. "Their food stamps may run out two weeks into the month.''

And when was the last time you made homemade chickpea dip? The market-basket of items the government uses to determine how much it costs a food stamp recipient to make "thrifty'' foods relies heavily on the purchase of raw ingredients such as beans, which are then to be miraculously transformed into meals made from scratch. It's a feat few middle-class families can accomplish these days. For most food stamp recipients - the disabled, the elderly and low-wage workers with long and sometimes unpredictable hours - it's mission impossible.

So the public-relations gaffe the USDA made just as the holiday season was beginning could turn out to be more of a blessing than a bungle. Congress is due to reauthorize the food stamp program next year - a task that would usually draw little attention.

Now we know the problem isn't really what we call those who are hungry. It's finding a better way to feed them.

Marie Cocco writes for the Washington Post Writers Group, 1150 15th St. NW, Washington, DC 20071. Send e-mail to [email protected].